Britain in decline? Panel discussion at the Oxford Literary Festival

I’m just back from a fun afternoon at the Oxford Literary Festival, where I had come in as a late substitution at a panel discussion chaired by the legendary Martin Bell, on the theme of “Britain in decline”. Also on the panel was the Booker-shortlisted novelist Andrew O’ Hagan, my fellow Icon-author Kieron O’ Hara, whose book on “Trust” was one of the many influences for “Don’t Get Fooled Again”, and the excellent Paul Kingsnorth, with whom I spoke at last year’s Radical Bookfair in Edinburgh.

I’m not convinced that there’s a generalised, across-the-board decline in the UK, and I also think there’s a natural human tendency to believe that things were so much better in the “good old days” even when they weren’t.

But within certain specific areas there are worrying signs of a change for the worse – perhaps most acutely within our political system. Few now doubt that lies were told by the UK government in 2002 and 2003, at the highest level, about the evidence of Iraqi “Weapons of Mass Destruction” . These lies formed the pretext for launching a war which killed hundreds of British soldiers, and thousands of Iraqi civilians – yet there appears to be no mechanism for holding those who misled the country (and its Parliament) personally to account. Worse, the lies have continued – on rendition, on Jack Straw’s complicity in torture in Uzbekistan, and – repeatedly – on official government statistics.

When, earlier this year, Justice Minister Jack Straw announced that he was using his powers to block the release of minutes of the UK cabinet meetings in the run-up to the Iraq war (meetings in which he, as the then-Foreign Secretary, would have featured prominently) – ostensibly on the basis that future cabinet ministers might feel unable to speak openly if they thought that their words might eventually be read by the people who voted for them and paid their salaries – one almost got the sense that he himself didn’t think that anyone would really believe that this was the genuine reason. He was in a position to use his powers to block the release of information that would certainly have embarrassed (and possibly incriminated) him – so naturally he was going to use those powers to cover his back. Once he’d made that the decision, the accompanying lie was perhaps the easiest part – after all he’d had plenty of practice.

While there’s clearly nothing new about politicians behaving dishonestly, back in 2003, many people went along with what the government was saying about Iraq precisely because they just couldn’t believe that our politicians would lie about something quite so big and important as the circumstances that could lead to a war. Many people I spoke to at the time had the sense that, in our democracy, there were some lines that the political class just wouldn’t cross. What’s worrying is that this feeling now seems to have been replaced with a grudging acceptance that our politicians will routinely lie to us whenever it suits them, and that there’s nothing much we can do about it.

Coupled with this, there seems to be a growing tendency for the government to cite “trump card” excuses, such as “national security” to evade scrutiny of key government decisions or to justify controversial government policies – such as the Attorney General’s decision to halt a criminal investigation into one of Britain’s major arms manufacturers – and a company with links to the Labour party – BAE.

Lastly, and perhaps most worryingly of all, there have been ever-increasing demands by the government for “sweeping powers” – ostensibly to fight terrorism – to lock people up without charge, ban demonstrations, and monitor and record all our email, phone call, and web browsing activities. These demands are almost always made with the assurance that the powers will only be used in rare and exceptional circumstances – but once passed into law they quickly become routine.

This is a problem because the more we chip away at our ability to scrutinise what the government’s up to, and the more arbitrary powers we allow them to wield, the more we create opportunities for corruption and abuse.

At the moment it seems that, too often within our political system, the benefits of lying outweigh the costs, and until that equation changes it seems unlikely that the situation will significantly improve. I made a similar

Kieron O’ Hara talked about the sense of disillusionment over the hopes that were raised when the current Labour government was first elected in 1997, and about the rise of the “database state”, while Paul Kingsnorth discussed the decline of local community institutions and the “blandification” of town centres, although Andrew O’ Hagan also warned against over-generalising beyond specifics, and discussed the pessimistic atmosphere of what he called “declinism” that he’d experienced growing up in Scotland during the 1970s.

On the major points, there was relatively little disagreement voiced between the panel members – though I suspect that this may also have stemmed from a reluctance to disrupt a good-natured discussion. The audience was more challenging – with one questioner arguing that society’s problems had more to do with a general decline in personal responsibility than the venality of politicians, which is after all nothing new. Another challenged us to say what, specifically, we proposed could be done about the problems that we had outlined. Andrew O’ Hagan gave a very clear answer, which I felt was among the best of the discussion, arguing that the level of dishonesty and silence-in-the-face-of-dishonesty that we had seen in recent years among government ministers was a significant change from the behaviour of previous regimes, and that one thing we could all do was vow never again to vote for any of the individuals – whose names are well known – who have behaved so disreputably.

David Davis on UK government complicity in torture

From The Guardian

Last week, the attorney general referred the case of Binyam Mohamed to the police. This confirms what many of us already knew or suspected, that there is a prima facie case to answer that government agents colluded in the torture of one or several of the detainees picked up in Pakistan. It is important to understand what is meant by “colluded” in this case. It does not mean that British agents wielded the instruments of torture or were present when the pain was being inflicted. But neither does it simply mean negligence, as was suggested by one ill-informed, so-called security specialist on the BBC.

What has happened is that British agents have co-operated with foreign powers when they had good reason to believe that they were torturing British citizens or residents, providing information and questions to these foreign governments. This often involved getting the foreign agencies to put questions A, B and C under torture, so that once they had the answers, British agents could turn up and put the same questions without torture.

Pakistani intelligence service agents have told researchers that this procedure was followed with several different subjects and several different British agents. This is not about one “rogue agent”. It is systemic… It is inconceivable that the requirement for a foreign secretary’s warrant was not included in the standard operating procedure of the agencies involved. Given the severity of the laws against torture, both British and international, it is also inconceivable that it was not clear that the law was being broken.

So one of two things has happened. Either a foreign secretary has approved complicity in torture, in which case that foreign secretary should be on a criminal charge, or the system has suffered a massive breakdown, in which case heads should roll at the agency. But it is going to be difficult for the police, even with access to all the papers and all the British officers, to get to the core of the breakdown. Indeed, that is not their job. They will be looking, quite properly, to bring a criminal case against an individual.

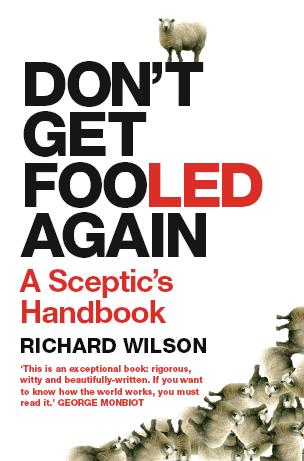

Don’t Get Fooled Again now available in paperback

I’m pleased to say that Don’t Get Fooled Again is out in paperback today and is available now from Amazon. The book looks at why it is that time and again, intelligent, educated people end up getting fooled by ideas that turn out on closer examination to be nonsense – from everyday high street scams to stock market bubbles and media spin, to the political delusions that led to the Iraq war and all that came with it.

Don’t Get Fooled Again has previously featured in The Guardian here and here, and you can also read online reviews here, here and here.

Telegraph newspaper denounces torture investigation

True to form, the Telegraph newspaper has roundly denounced the news that there is to be a criminal investigation into allegations of complicity in torture by the UK security services, and urged the Attorney General – a political appointee – to intervene in the judicial process in order to stop the investigation.

In the run-up to the 2003 Iraq invasion, and during the subsequent campaign by Bush administration hardliners to convince the world of the need for a war against Iran, the Telegraph security commentator Con Coughlin famously published a series of articles containing false and misleading information that appears to have been fed to him directly by the intelligence services. Now that those same intelligence services risk facing serious public scrutiny, the Telegraph is leading the calls to get the criminal investigation stopped.

African Union sends man who oversaw 300,000 deaths in South Africa to investigate reports of 300,000 deaths in Darfur – assisted by the man who oversaw 300,000 deaths in Burundi

Hot on the heels of its anguished denunciation of the international indictment of Sudanese President Omar Bashir over war crimes and crimes against humanity in Darfur, the African Union has further cemented its global credibility by appointing ex-South African President Thabo Mbeki to look into the charges.

Mbeki is certainly an interesting choice for a mission whose ostensible aim is to establish the truth about a life-or-death humanitarian issue.

As President of South Africa, Mbeki famously bought into the claims of internet conspiracy theorists who say that HIV does not cause AIDS, and that the illness is actually caused by the medications used to treat the disease. A Harvard study recently concluded that the Mbeki government’s steadfast refusal to make AIDS medicines available to those with HIV may have led to over 330,000 preventable deaths.

To add further gravitas, Mbeki will be assisted, according to Voice of America (who give a slightly different account of the purpose of the mission), by the former President of Burundi, Major General Pierre Buyoya.

Buyoya is widely suspected of orchestrating the 1993 assassination of the man who had defeated him at the ballot box earlier that year, the country’s first democratically-elected Hutu President, Melchior Ndadaye. The killing triggered a brutal, decade-long ethnic war in which more than 300,000 people, mostly civilians, are believed to have died.

For most of this period, Buyoya was in charge, having seized the Presidency in a coup in 1996. During Buyoya’s reign, forces under his command carried out a series of brutal massacres against the Hutu civilian population – but as the International Criminal Court can only investigate crimes committed after 2003 – the year Buyoya’s rule ended, it’s unlikely that he will face justice any time soon. A long promised UN-aided “special court” for Burundi has yet to materialise.

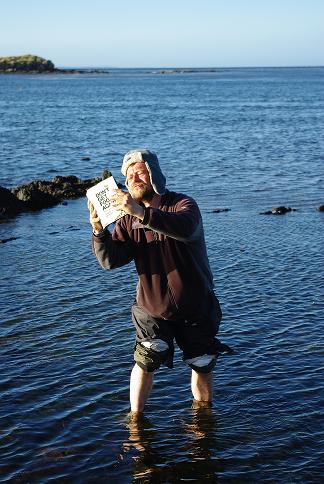

“Don’t Get Fooled Again” reaches the Falkland Islands

In October last year, as regular readers of this blog will know, several copies of “Don’t Get Fooled Again” were placed in glass jars, and floated seawards down the river Thames, with a note in English, French and Spanish asking anyone who found them to get in touch.

I had more or less given up hope of ever hearing anything further, when a package arrived this weekend containing two rather odd photographs. There was no letter or note, but the post-mark indicates that the package originated in the Falkland Islands, in the far-flung reaches of the South Atlantic.

I’m at something of a loss to know what to make of these two photos, but I’m including them in this post in the hope that someone reading this will be able to give me some ideas.

Update – 2nd April 2009 – as many readers have guessed, the above account is not wholly accurate…

Mark Hoofnagle on climate change denial

From The Guardian

At denialism blog we have identified five routine tactics that should set your pseudo-science alarm bells ringing. Spotting them doesn’t guarantee an argument is incorrect – you can argue for true things badly – but when these are the arguments you hear, be on your guard.

• First is the assertion of a conspiracy to suppress the truth. This conspiracy invariably fails to address or explain the data or observation but only generates more unexplained questions.

But let us think about such conspiracies for a moment. Do they stand up to even a cursory evaluation? Is it really possible to make thousands of scientists, from over 100 countries, and every national academy of every country toe the same line, falsify data, and suppress this alleged dissent? I certainly didn’t get the memo. At the heart of all denialism are these absurd conspiracy theories that require a superhuman level of control of individuals that simply defies reality.

• The second tactic is selectivity, or cherry-picking the data. Creationists classically would quote scientists out of context to suggest they disagreed with evolution. Global warming denialists similarly engage in this tactic, harping on about long discredited theories and the medieval warming period ad nauseum. But these instances are too numerous and tedious to go into in depth.

• Instead, let’s talk about the third tactic, the use of fake experts, where both creationists and global warming denialists truly shine. Creationists have their Dissent from Darwin list of questionable provenance. Similarly, global warming denialist extraordinaire has his list of climate scientists who disagree with global warming.

But don’t look too close! Lots of his big names are the same hacks who used to deny that cigarettes cause cancer for the tobacco companies, others are scientists who are wrongly included because they said something that was quoted out of context, others simply have no credibility as experts on climate like TV weathermen. But the desire of denialists to gain legitimacy by the numbers of scientists (or whoever they can find with letters after their name) used remains despite their contempt for the science they disagree with.

• The fourth tactic – moving goalposts or impossible expectations – is the tendency to refuse to accept when denialists’ challenges to the science have been addressed. Instead, they just come up with new challenges for you to prove before they say they’ll believe the theory. Worse, they just repeat their challenges over and over again ad nauseum.

This may be their most frustrating tactic because every time you think you’ve satisfied a challenge, they just invent a new one. The joke in evolutionary biology is that every time you find a transitional fossil all you do is create two new gaps on the fossil record, one on either side of the discovery. Similarly with global warming denialism, there is no end to the challenges that denialists claim they need to have satisfied before they’ll come on board.

It’s important to recognise that you shouldn’t play their game. They’ll never be satisfied because they simply don’t want to believe the science – for ideological reasons. In the US, global warming denialism usually stems from free-market fundamentalism that is terrified of regulation and any suggestion there should be control of business.

• Finally, the fifth tactic is the catch-all of logical fallacies. You know you’ve heard them. Al Gore is fat! His house uses lots of energy! Evolutionary biologists are mean! God of the gaps, reasoning by analogy, ad hominem, you name it, these arguments, while emotionally appealing, have no impact on the validity of the science.

Justice not therapy…

Vintage stuff by Ken Roth and the late great Alison Des Forges, in defence of the basic principles of international justice, and individual responsibility. From the Boston Review:

[Helena] Cobban argues that criminal prosecutions are a “strait-jacket” solution imposed from outside Rwanda. But the Rwandan government itself initially requested the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (though it later opposed it) and decided on national trials for the more than 100,000 jailed in Rwanda on charges of genocide…

Cobban’s analysis is most troubling when she resorts to medical metaphor. She acknowledges the planning and organization of the genocide by state authorities, detailing how killers coolly and regularly slaughtered Tutsis as daily “work.” Yet in her view, these were not horrible crimes but a “social psychosis,” not acts of volition but a “collective frenzy”; the architects of the genocide are not more culpable than ordinary killers but “sicker.”

Cobban’s analysis resembles that of the perpetrators themselves. They argued that the slaughter was “spontaneous,” committed by people driven mad out of fear and anger. Rwandan killers have indeed been traumatized but their ailment resulted from their conduct rather than causing it.

Mob psychology cannot explain choices made during the genocide: why some individuals killed for reward or pleasure, or from fear of punishment, while others did not. To judge the killers as merely “sick” devalues the courage and decency of the millions who resisted this inhumanity, sometimes at the cost of their lives.

Cobban’s medical metaphor allows no place for individual responsibility. A person plagued by cancer is a victim of unfortunate circumstance, but is not at fault. Murderers, let alone orchestrators of genocide, are different. When they corral victims into churches and stadiums and systematically slaughter them with guns and machetes, the killers are not the latest hapless victims of the genocidal flu. They are deliberate, immoral actors. Treating them as no more culpable than children who refuse to wear coats and catch cold is both wrong and dangerous. Wrong because it does a deep disservice to the victims, as if their deaths were a natural accident, not a deliberate choice. Dangerous because it signals to other would-be mass murderers that they risk not punishment but, at most, communal therapy sessions.

“Unskilled and Unaware of It: How Difficulties in Recognizing One’s Own Incompetence Lead to Inflated Self-Assessments”

From The American Psychological Association

People tend to hold overly favorable views of their abilities in many social and intellectual domains. The authors suggest that this overestimation occurs, in part, because people who are unskilled in these domains suffer a dual burden: Not only do these people reach erroneous conclusions and make unfortunate choices, but their incompetence robs them of the metacognitive ability to realize it…

In 1995, McArthur Wheeler walked into two Pittsburgh banks and robbed them in broad daylight, with no visible attempt at disguise. He was arrested later that night, less than an hour after videotapes of him taken from surveillance cameras were broadcast on the 11 o’clock news. When police later showed him the surveillance tapes, Mr. Wheeler stared in incredulity. “But I wore the juice,” he mumbled. Apparently, Mr. Wheeler was under the impression that rubbing one’s face with lemon juice rendered it invisible to videotape cameras…

UK government implicated in torture

From The Guardian

A policy governing the interrogation of terrorism suspects in Pakistan that led to British citizens and residents being tortured was devised by MI5 lawyers and figures in government, according to evidence heard in court.

A number of British terrorism suspects who have been detained without trial in Pakistan say they were tortured by Pakistani intelligence agents before being questioned by MI5. In some cases their accusations are supported by medical evidence.

The existence of an official interrogation policy emerged during cross-examination in the high court in London of an MI5 officer who had questioned one of the detainees, Binyam Mohamed, the British resident currently held in Guantánamo Bay.

Alison Des Forges

Earlier this week I had an invitation to a public meeting in London at which the renowned Human Rights Watch investigator Alison Des Forges would be speaking. Alison had taken a close interest in the December 2000 massacre which claimed 21 lives in Burundi, including that of my sister Charlotte. She had been enormously encouraging of our efforts to secure justice, and gave warm and generous feedback when “Titanic Express” was published in 2006. We’d been in touch a number of times over the years but I’d never met her in person.

In the months after Charlotte’s death, when I was desperately trying to understand the background to the brutal regional conflict which had claimed her life – and in the years that followed- I also learned a huge amount from the wealth of material that Alison Des Forges has written, such as the extraordinary book (the full text of which is available online at the HRW website) “Leave None to Tell the Story”.

I wanted to go to Wednesday’s meeting but wasn’t able to make it. One always assumes there will be another opportunity. This morning I was devastated to read that, on her return from Europe, Alison Des Forges had been killed in the plane crash in New York State on Thursday evening. The news was announced by Human Rights Watch yesterday:

“Alison’s loss is a devastating blow not only to Human Rights Watch but also to the people of Rwanda and the Great Lakes region,” said Kenneth Roth, executive director of Human Rights Watch. “She was truly wonderful, the epitome of the human rights activist – principled, dispassionate, committed to the truth and to using that truth to protect ordinary people. She was among the first to highlight the ethnic tensions that led to the genocide, and when it happened and the world stood by and watched, Alison did everything humanly possible to save people. Then she wrote the definitive account. There was no one who knew more and did more to document the genocide and to help bring the perpetrators to justice.”

Des Forges, born in Schenectady, New York, in 1942, began working on Rwanda as a student and dedicated her life and work to understanding the country, to exposing the serial abuses suffered by its people and helping to bring about change. She was best known for her award-winning account of the genocide, “Leave None to Tell the Story,” and won a MacArthur Award (the “Genius Grant”) in 1999. She appeared as an expert witness in 11 trials for genocide at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, three trials in Belgium, and at trials in Switzerland, the Netherlands, and Canada. She also provided documents and other assistance in judicial proceedings involving genocide in four other national jurisdictions, including the United States.

Clear-eyed and even-handed, Des Forges made herself unpopular in Rwanda by insisting that the rebel Rwandan Patriotic Front forces, which defeated the genocidal regime, should also be held to account for their crimes, including the murder of 30,000 people during and just after the genocide. The Rwandan government banned her from the country in 2008 after Human Rights Watch published an extensive analysis of judicial reform there, drawing attention to problems of inappropriate prosecution and external influence on the judiciary that resulted in trials and verdicts that in several cases failed to conform to facts of the cases.

“She never forgot about the crimes committed by the Rwandan government’s forces, and that was unpopular, especially in the United States and in Britain,” said Roth. “She was really a thorn in everyone’s side, and that’s a testament to her integrity and sense of principle and commitment to the truth.”

Des Forges was not only admired but loved by her colleagues, for her extraordinary commitment to human rights principles and her tremendous generosity as a mentor and friend.

“Alison was the rock within the Africa team, a fount of knowledge, but also a tremendous source of guidance and support to all of us,” said Georgette Gagnon, Africa director at Human Rights Watch. “She was almost a mother to us all, unfailingly wise and reasonable, absolutely honest yet diplomatic. She never seemed to get stressed out, in spite of the extreme violence and horror she had to deal with daily. Alison felt the best way to make things better was to be relentlessly professional and scrupulously fair. She didn’t sensationalize; her style was to let the victims speak for themselves.”

Corinne Dufka, another colleague who worked closely with Des Forges, wrote: “She always found the time to listen and helped me see outside the box. Alison inspired me to be a better researcher, a better colleague, a more giving mentor and a more balanced human being. She was also funny – her sardonic sense of humor, usually accompanied with that sparkle in her eye, lightened our burden.”

An historian by training, Des Forges wrote her PhD thesis on Rwanda and spent most of her adult life working on the Great Lakes region, despite an early stint in China with her husband, Roger, a professor of history and China expert at the University of Buffalo.

Des Forges graduated from Radcliffe College in 1964 and received her PhD from Yale in 1972. She began as a volunteer at Human Rights Watch, but was soon working full-time on Rwanda, trying to draw attention to the genocide she feared was looming. Eventually, Roth had to insist she take a salary. She co-chaired an international commission looking at the rise of ethnic violence in the region and published a report on the findings several months before the genocide. Once the violence began, Des Forges managed to convince diplomats in Kigali to move several Rwandans to safety, including the leading human rights activist Monique Mujawamariya.

As senior adviser to the Africa division at Human Rights Watch since the early 1990s, Des Forges oversaw all research work on the Great Lakes region, but also provided counsel to colleagues across the region and beyond. She also worked very closely with the International Justice Program because of all her involvement with the Rwanda tribunal.

“The office of the prosecutor relied on Alison as an expert witness to bring context and background and detailed knowledge of the genocide,” Roth said. “Her expertise was sought again and again and again by national authorities on cases unfolding in their courts of individuals facing deportation, or on trial for alleged involvement in the genocide.”

Most recently, Des Forges was working on a Human Rights Watch report about killings in eastern Congo.

Update – I was looking again just now at the online version of “Leave None To Tell The Story”. Since I first read it, back in 2001, Alison wrote an updated foreword, which gives one of the clearest explanations I’ve seen of the links between what took place in Rwanda, and the lesser-known conflicts in Burundi and the DRC:

In mid-1994 officials of the former [Rwandan] government, soldiers, and militia fled to the Congo, leading more than a million Rwandans into exile. They carried with them their ideology of Hutu supremacy and many of their weapons. They sought the support of local Congolese people as well as of the government, hoping to broaden their base for continued resistance against the RPF. They insisted that Rwandan Hutu and different Congolese groups were a single “Bantu” people because they spoke similar languages and shared some cultural traits. They said Tutsi were “Nilotic” invaders who, together with the related Hima people of Uganda, intended to subjugate the “Bantu” inhabitants. This “Bantu” ideology – and the RPF determination to counter it – informed the framework for much of the military conflict in the region for the next ten years.

In 1996 Rwanda and Uganda, led by President Yoweri Museveni, invaded the Congo. Rwanda wanted to eliminate any possible threat from the former Rwandan army and militia who were re-organizing and re-arming in refugee camps in eastern Congo. Uganda sought greater political influence and control over resources in the region. Together with their Congolese allies, the Rwandan and Ugandan troops moved rapidly westward, at first hunting down the remnants of the Rwandan Hutu from the refugee camps – combatants and civilians alike – but then setting another objective, that of overturning Mobuto and his government. They succeeded, but in 1998 the new Congolese government, led by Laurent Desire Kabila, turned against its former supporters. Kabila told the Rwandan and Ugandan troops to go home, thus provoking a new war. This second Congo war at one point involved seven African nations and a host of rebel movements and other local armed groups, all fighting to control the territory and vast wealth of the Congo. Casualties among civilians were enormous, from lack of food, medical care, and clean water as well as from direct attack by the various forces.

The real nature of this war, like that of the first, was for a long time disguised by the references to the genocide. In demanding a return to national sovereignty Congolese officials spoke in anti-Tutsi language and crowds in Kinshasa killed Tutsi on the streets. Rwanda sought to justify making war by claiming the need to eliminate perpetrators of the genocide who were operating in eastern Congo with the support of the Congolese government. Rwandan authorities continued to stress this supposed security threat from the other side of the border long after the numbers and resources of the former Rwandan army and militia had diminished and their members were widely scattered.

In 1997 and 1998, in the hiatus between the two Congo wars, soldiers and militia of the genocidal government, supported by thousands of new recruits, crossed from the Congo and led an insurrection in northwestern Rwanda. The RPF forces suppressed the rebellion at the cost of tens of thousands of lives, many of them civilians who happened to live in the area. A substantial number of the rebel combatants had not taken part in the genocide and seemed more focused on overturning the government than on hunting down Tutsi civilians, but others continued to harbor genocidal intentions and singled out Tutsi to be attacked and killed.

Events in Burundi, a virtual twin to Rwanda in demographic terms, first influenced and then were influenced by the Rwandan genocide. Burundi was already immersed in its own crisis with widespread ethnic slaughter in late 1993. These killings, as well as international indifference to them, spurred genocidal planning in Rwanda. After April 1994 Burundians viewed with horror the massacres of others of their own ethnic group in Rwanda, Tutsi identifying with victims of the genocide and Hutu identifying with those killed by RPF forces. Burundian Tutsi and Hutu feared and distrusted each other more because of the slaughter in Rwanda and each group vowed that its members would not be the next victims. Former Rwandan soldiers and militia at times joined Burundian Hutu rebel forces, bringing them military expertise and reinforcing their anti-Tutsi ideas. RPF soldiers on occasion came south to help the Burundian army prevent a victory by Hutu rebels.

Within Rwanda the RPF used the pretext of preventing a recurrence of genocide to suppress the political opposition, refusing to allow dissidents to organize new political parties and eliminating an existing party that could potentially have challenged the RPF in national elections. Authorities jailed dissidents and drove others into exile on charges of “divisionism,” equated to an incipient form of genocidal thinking even when opponents sought to construct parties that included Tutsi as well as Hutu. During 2003, under RPF leadership, Rwandans adopted a new constitution that enshrined a vague prohibition of “divisionism” and made liberties of speech, press, and association subject to regulation – and possible limitation – by ordinary law. In presidential and legislative elections, the RPF came close to asserting that a vote for others was a vote for genocide – past or future. With such a campaign theme and with a combination of intimidation and fraud, the RPF re-affirmed its dominance of political life.

In the years just after the end of the genocide, many international leaders supported the RPF as if hoping thus to compensate for their failure to protect Tutsi during the genocide. Even when confronted with evidence of widespread and systematic killing of civilians by RPF soldiers in Rwanda and in the Congo, most hesitated to criticize these abuses. Not only did they see the RPF as the force that had ended the genocide but they also saw all opponents of the RPF as likely to be perpetrators of genocide, an assessment that was not accurate either in 1994 or later. So long as the parties were defined this way, international leaders acquiesced inÑor even actively supportedÑthe RPF activities in the Congo. Similarly international actors frequently tolerated RPF limits on civil and political freedom inside Rwanda, readily conceding the RPF argument that the post-genocidal context justified restrictions on the usual liberties.

As the ten years after the genocide drew to a close, the international community moderated its support of the current Rwandan government and exerted considerable pressure to obtain withdrawal of its troops from the Congo. Some international leaders began to question the tight RPF control within Rwanda; diplomats and election observers from the European Union and the United States noted abuses of human rights that marred the 2003 elections. Despite these signs of growing international concern, the RPF-led government appeared firmly seated for the near future. Whether it will be able to assure long-term stability and genuine reconciliation may depend on its ability to distinguish between legitimate dissent and the warning signs of another genocide.

Human Rights Watch reissues this book – substantially the same as the original printing – to ensure that a detailed history of the genocide remains available to readers. Since its first publication in English and French, the book has appeared in German and will shortly be published in Kinyarwanda, the language of Rwanda. The horrors recorded here must remain alive in our heads and hearts; only in that way can we hope to resist the next wave of evil.

Rachel Reid on the UK media’s uncritical repetition of government smears

From Human Rights Watch

Whatever the MoD has whispered into the ear of the Sun, Col McNally and I met only twice, both times in a purely professional capacity, both times at the Nato military HQ in Kabul. Both times we met to talk about civilian casualties from US and Nato air strikes.

What has happened in the last couple of days has been bewildering. I do not understand how these two meetings might have led the British government to accuse McNally of a serious crime that could lead to a hefty jail sentence, and why my government might want to see my reputation dragged through the mud, when I live in a country where a woman’s reputation can mean her life. The meetings seemed unexceptional. A QC retained by Human Rights Watch has confirmed that the kind of information I received is not covered by the Official Secrets Act.

If the ministry had been seriously concerned that one of their officers was leaking information, why leak it to the media? Why was my name released to the media by the MoD, with a (nudge, nudge, wink, wink) libel that our relationship was “close”? They would know exactly what impression they were creating, and presumably decided that my reputation was expendable in order to ensure coverage of their “story”.

Why did journalists from the Sun, the Times and the Mail write this as a story focusing on the MoD’s entirely bogus suggestion that I had some kind of “relationship” with McNally? Why is it that my photograph was published? Why have journalists not been asking questions about why the MoD has been encouraging them to publish a vicious, false slur about me in order stop me from doing my job for Human Rights Watch in asking for information from the Nato official in charge of monitoring civilian casualties?

Living in Afghanistan, where democracy, a free media, freedom of information and freedom of expression are still a faraway dream, I have developed a deep appreciation of the freedoms I grew up believing I had in Britain. I expect better from my own government and from the British media that I used to be a part of.

HRW investigator smeared by UK government’s “unnamed sources”

From The Observer:

Does “on the ground female human rights worker” equate with “slut” these days? Are they perceived as wandering around war zones in cocktail dresses slashed to the thigh, hungry for the next thrill, perhaps a hunky military man to devour, humming the old toe-tapper I Love a Man in Uniform? Or could it be possible that these women pour all their passion and intensity into their jobs?

I only ask because of the curious case of Rachel Reid, a researcher for Human Rights Watch in Afghanistan. Last week, it emerged that a senior army officer, Colonel Owen McNally, had been arrested under the Official Secrets Act for allegedly passing classified information to a human rights worker. Unnamed sources were quick to inform the media that McNally was known to be “close” to Reid, who had divulged the secrets after she “befriended him”.

Writing in response, Reid says that, far from being “close” to McNally, she met him twice professionally at the military HQ in Kabul to discuss civilian casualties. (Interestingly, Reid had angered Nato by pointing out that these deaths had tripled between 2006-7.)

Now Reid is horrified that her reputation has been dragged through the mud when she is living in a country “where a woman’s reputation can mean her life”. She is devastated by the “vicious slur” leaked to the media, saying: “They knew exactly what impression they were creating.” Quite. And is anyone else getting deja vu?

As McNally’s investigation is still going on, the full facts have yet to emerge. However, to me, this seems eerily reminiscent of Andy Burnham’s description of MP David Davies and Liberty’s Shami Chakrabarti’s “late-night, hand-wringing, heart-melting phone calls” last year.

Intended or not, the impression given was that Chakrabarti and Davies were steaming up Westminster’s windows about more than the 42-day detention period. Briefly but indelibly, Chakrabati was no longer just a human rights professional, she was a femme fatale, pouting and wriggling through the corridors of power.

Is it wrong to call AIDS denialists “AIDS denialists”?

People commonly referred to as “AIDS denialists” tend to prefer the description “AIDS sceptics”, “AIDS rethinkers” or “AIDS dissidents”, with some regarding “AIDS denialism” as a pejorative term, on a par with racial slurs.

Chris and Mark Hoofnagle define denialism as:

the employment of rhetorical tactics to give the appearance of argument or legitimate debate, when in actuality there is none. These false arguments are used when one has few or no facts to support one’s viewpoint against a scientific consensus or against overwhelming evidence to the contrary. They are effective in distracting from actual useful debate using emotionally appealing, but ultimately empty and illogical assertions.

If “pejorative” is defined as “having a disparaging, derogatory, or belittling effect or force”, then “AIDS denialist” would certainly seem to fit the bill – but does that mean that it’s wrong to use the term?

It seems to me that this really depends on whether or not “denialism” is an accurate description of the behaviour of the people-commonly-known-as-AIDS-denialists. There are plenty of terms in our language that have a disparaging meaning – “liar”, “alarmist”, “criminal”, “conspiracy theorist”, “bigot”, “crank” etc. – but that doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s always wrong to use them. It would clearly be unfair to describe as a”liar” someone who had lived a life of impeccable honesty. But where a person appears knowingly to have engaged in a systematic campaign of deception, an insistence on the use of a neutral, non-perjorative, term to describe them and their behaviour would actually be a watering down of the truth, and may even be seized on as a validation of their actions.

This is really the problem I have with labels like “AIDS sceptic” (or “AIDS skeptic”). The website “UK-skeptics” defines “skepticism” as “an honest search for knowledge”. To describe those who deny the evidence linking HIV and AIDS as “sceptics” seems therefore to presuppose that they are both honest, and genuinely searching for knowledge (rather than seeking to defend a particular ideological position), which many would dispute.

The term “AIDS dissident” is arguably even worse, conjuring, as it does, images of Soviet-era democracy campaigners being rounded up and imprisoned for speaking the truth to a dogmatic, authoritarian establishment. Those battling to convince the world that HIV is not the cause of AIDS may well see themselves in a similar light, but in reality there have been no jailings or show trials – and 101 badly-formatted websites testify to the unfettered freedom with which the self-described “dissidents” have been able to make their case.

“AIDS rethinker” is perhaps the least objectionable term – but again its accuracy seems questionable, as it suggests a willingness to rethink one’s ideas which many would argue is precisely what is lacking in those who deny the link between AIDS and HIV. It also seems rather broad. AIDS scientists are continually rethinking and redeveloping their ideas about the disease as new data comes along, and could therefore quite reasonably be described as “AIDS rethinkers” too. If we’re looking for an alternative term that uniquely identifies those commonly referred to as “AIDS denialists”, then “AIDS rethinker” seems to obfuscate matters rather than clarify them.

None of the commonly-used terms for describing those who deny the link between HIV and AIDS seem to me to be value-neutral. “AIDS denialist” is a term with negative connotations – but I’m not sure that this matters. If those negative connotations are justified, then the term is accurate. And when we’re dealing with a problem as serious as HIV and AIDS, accuracy is arguably more important than sparing the feelings of a group of dangerous and misguided people.

See also: The parallels between AIDS denial and Holocaust negationism

Is it wrong to highlight the deaths of HIV-positive AIDS denialists who reject medications and urge others to do the same?

In “Don’t Get Fooled Again”, I look at the role played by the media in promoting dangerous pseudo-scientific ideas under the guise of “balance” in reporting. From the mid-1950s onwards, there was a clear consensus among scientists, based on very strong epidemiological evidence, that smoking caused lung cancer. Yet for several decades, many journalists insisted on “balancing” their reports on each new piece of research with a quote from an industry-funded scientist insisting that the case remained “unproven”.

The tobacco industry’s strategy from an early stage was not to deny outright that smoking was harmful, but to maintain that there were “two sides to the story”. In January 1954, the industry issued its now-famous “Frank Statement to Cigarette Smokers” – a full-page advertisement published in 50 major newspapers across the US.

“Recent reports on experiments with mice have given wide publicity to a theory that cigarette smoking is in some way linked with lung cancer in human beings”

the industry noted.

“Although conducted by doctors of professional standing, these experiments are not regarded as conclusive in the field of cancer research… we feel it is in the public interest to call attention to the fact that eminent doctors and research scientists have publicly questioned the claimed significance of these experiments.”

The strategy played cleverly to the media’s penchant for “controversy”, and proved remarkably successful. Long after the matter had been decisively settled among scientists, public uncertainty around the effects of smoking endured.

US cigarette sales continued rising until the mid-1970s – and it was only in the 1990s – four decades after the scientific case had been clearly established – that lung cancer rates began to tail off. Harvard Medical Historian Allan M Brandt has described the tobacco industry’s public deception – in which many mainstream journalists were complicit – as “the crime of the century”:

It is now estimated that more that 100 million people worldwide died of tobacco-related diseases over the last hundred years. Although it could be argued that for the first half of the century the industry was not fully aware of the health effects of cigarettes, by the 1950s there was categorical scientific evidence of the harms of smoking.

The motivations of the AIDS denialists may be very different, but their rhetoric and tactics are strikingly similar. During the early 1990s, Sunday Times medical correspondent Neville Hodgkinson was bamboozled into running a series of articles – over a period of two years – claiming that:

“a growing number of senior scientists are challenging the idea that the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) causes AIDS”…

“This sensational possibility, now being contemplated by numerous doctors, scientists and others intimately concerned with the fight against the disease, deserves the widest possible examination and debate.”

Hodgkinson declared in December 1993.

“Yet it has been largely ignored by the British media and suppressed almost entirely in the United States… The science establishment considers itself on high moral ground, defending a theory that has enormous public health implications against the ‘irresponsible’ questioning of a handful of journalists. Their concern is human and understandable, even if we might expect our leading scientists to retain more concern for the truth while pursuing public health objectives.”

As with the tobacco industry’s “scepticism” over the link between smoking and cancer, the views promoted by Hodgkinson tended to focus on gaps in the established explanation (many of which have since been filled) rather than on any empirical research showing an alternative cause. But he did use one of the recurrent rhetorical motifs of the AIDS denial movement – highlighting the case of an HIV-positive “AIDS dissident” who refused to take anti-retroviral drugs but remained healthy.

Jody Wells has been HIV-positive since 1984. He was diagnosed as having AIDS in 1986. Today, seven years on, he says he feels fine with energy levels that belie his 52 years. He does not take the anti-HIV drug AZT…

He feels so strongly about the issue that he works up to 18 hours a day establishing a fledgling charity called Continuum, “an organisation for long-term survivors of HIV and AIDS and people who want to be”. Founded late last year, the group already has 600 members.

Continuum emphasises nutritional and lifestyle approaches to combating AIDS, arguing that these factors have been grossly neglected in the 10 years since Dr. Robert Gallo declared HIV to be the cause of AIDS.

Tragically – if predictably – Jody Wells was dead within three years of the article being written.

Although Hodgkinson left the Sunday Times in 1994, his articles on the “AIDS controversy” continued to be disseminated online, lending valuable credibility to the denialist cause – and have been credited with influencing Thabo Mbeki’s embrace of AIDS denial in the early part of this decade.

When, in 2000, President Mbeki invited several leading denialists to join his advisory panel on HIV and AIDS, Hodgkinson was one among a number who published articles in the South African media praising the decision. Writing in the New African, Hodgkinson called for “a humble, open, inquiring approach on all sides of this debate” – whilst simultaneously declaring that “AZT is a poison” and denouncing “the bankruptcy of AIDS science”.

Hodgkinson also wrote for Continuum’s magazine, which, following Jody Wells’ death was edited by HIV-positive medication refusnik Huw Christie. Christie defiantly launched the “Jody Wells Memorial Prize” (recently satirised here by Seth Kalichman) offering £1,000 to anyone who could prove to his satisfaction that HIV was real.

The magazine finally folded in 2001, with the Jody Wells Memorial Prize still on offer, after Huw Christie died from a disease which fellow denialists insisted was not AIDS-related. “Neither of your illnesses would have brought you down, Huw”, wrote Christie’s friend Michael Baumgartner in 2001. “You simply ran out of time to change gear. We both knew it did not need some ill-identified virus to explain your several symptoms”.

“Huw’s devotion to life has no doubt contributed to a better understanding of AIDS and he saved many who, without hearing a skeptical voice, would have been stampeded down the path of pharmaceutical destruction”

wrote HIV-positive San Francisco AIDS “dissident” David Pasquarelli.

“I readily acknowledge that if it wasn’t for the work of Huw and handful of other AIDS dissidents, I would not be alive today”.

Pasquarelli died at the age of 36 three years later.

The same document includes a tribute from Christine Maggiore, another HIV-positive AIDS “sceptic” who famously rejected medication, and publicly urged others to do the same. As has been widely reported, Maggiore died last month of an illness commonly associated with AIDS.

Connie Howard, writing in today’s edition of VUE Weekly, finds the reaction to Maggiore’s passing distasteful, claiming that: “some AIDS activists are celebrating—not her death exactly, but celebrating a point for their team nonetheless”.

Howard suggests, echoing Hodgkinson, that “Many HIV-positive people who choose an alternative holistic health route defy all odds and stay well and symptom-free for decades”, and that she has “talked to HIV-positive people living well—really well—without drugs.”

According to Howard:

“it’s time that choice and discussion become possible without hate instantly becoming the most potent ingredient in the mix… The vitriol delivered the way of both dissidents and the reporters telling the stories of the dissidents is a crime… Christine Maggiore deserves to have chosen her own path and to be respected for it.”

AIDS denialists and their sympathisers often accuse mainstream AIDS researchers of not being open to “discussion” or “debate”. Yet meaningful discussion is only possible when both sides are operating in good faith. The problem with AIDS and HIV is that the evidence linking the two is so overwhelmingly strong that the only way to maintain a consistently denialist position is to engage in “bogus scepticism” – arbitrarily dismissing good evidence that undermines one’s favoured viewpoint, misrepresenting genuine research in order to create the appearance of controversy where there is none, seeking to give unpublished amateur research equal status with peer-reviewed studies by professional scientists, and treating minor uncertainties in the established theory as if they were knock-down refutations. In such circumstances, reasoned debate simply becomes impossible.

Howard doesn’t specify which AIDS activists she believes “view the death of an AIDS dissident as a victory” or have celebrated Maggiore’s passing, so it’s difficult to evaluate the truth of that particular claim.

But the notion that everyone is duty bound to “respect” Christine Maggiore’s decision to embrace AIDS denial – and counsel others to do the same – does seem a tad problematic.

What Howard chooses not to tell her readers is that Maggiore’s denial extended not only to refusing medical treatment for herself – she also declined to take measures to mitigate the risk of transmission to her young daughter, Eliza Jane, and refused to have her tested or treated for HIV. When Eliza Jane died in 2005 of what a public coroner concluded was AIDS-related pneumonia, Maggiore refused to accept the result, attacked the coroner’s credibility, and claimed that the verdict was biased.

Missing too, is any reference to South Africa, where Maggiore travelled in 2000 to promote her ideas on AIDS and HIV. Maggiore is said to have personally influenced Thabo Mbeki’s decision to block the provision of anti-retroviral drugs to HIV-positive pregnant women. A Harvard study recently concluded that this decision alone resulted in 35,000 more babies being infected with HIV than would otherwise have been the case. Overall, the study concluded, Mbeki’s denialist policies had led to more than 300,000 preventable deaths.

If the Harvard researchers are correct, then AIDS denialism – of which Christine Maggiore was a vocal proponent – has already caused many more deaths than did the war in Bosnia during the early 1990s. Yet the only “crime” that Connie Howard seems prepared to acknowledge in relation to AIDS and HIV is the ill-feeling directed towards Christine Maggiore, her fellow “dissidents”, and the journalists who give space to their denialist views – views which have repeatedly been shown to be based not on science, but on “selective reading of the scientific literature, dismissing evidence… requiring impossibly definitive proof, and dismissing outright studies marked by inconsequential weaknesses”.

Should we “respect” a person’s decision to refuse medical treatment, even if that leads to their own premature death? Arguably we should. But should we also respect that same person’s decision, on ideological grounds, to deny medical treatment to a young child, with fatal consequences? Should we respect their decision to support a pseudo-scientific campaign denying the established facts about a serious public health issue, when that campaign results in hundreds of thousands of deaths?

It is surely possible to agree that Christine Maggiore’s premature death was an appalling human tragedy, whilst pointing out that she was nonetheless dangerously misguided – and that the manner of her passing makes the tragedy all the more poignant.

Christine Maggiore, Jody Wells, Huw Christie, and David Pasquarelli form part of a grim roll-call of HIV-positive medication refusniks who chose to argue publicly that the state of their health cast doubt on the established science around AIDS and HIV, and then went on to die from the disease. For AIDS activists to remain silent in such circumstances would be a dereliction of duty. Publicly highlighting the human cost of AIDS denial, so that similar deaths may be prevented in future, must surely take precedence over showing “respect” to dangerously misguided people, however tragic the circumstances of their demise.

See also: The parallels between AIDS denial and Holocaust negationism

Christine Maggiore’s last podcast

Yesterday I listened, in growing disbelief, to the last episode of HIV-positive AIDS denialist Christine Maggiore’s regular podcast, “How Positive Are You?”. The programme is dated December 6th, just 3 weeks before Maggiore’s sudden death from pneumonia, although comments in the podcast itself suggest it was recorded the previous month.

The discussion is co-presented by David Crowe, who early in the programme recounts with pride some of the comments he has received via email. He’s particularly pleased about one from an HIV-positive listener who reads the “Alive and Well” website every day, and who has chosen to disregard his doctor’s advice, forgoing anti-retroviral drugs in favour of eating lots of nutritious food and breathing plenty of fresh air. “Wow, that’s beautiful”, Maggiore gushes.

Later on, Crowe and Maggiore conduct a phone interview with AIDS clinician Dr. Jocelyn Dee, who had (along with several colleagues) advised the makers of the TV drama “Law and Order SVU”. In October last year, the programme featured a fictional tragedy strikingly similar to that which hit Maggiore’s family in 2005, when her young daughter died suddenly from what a coroner later determined to be AIDS-related pneumonia. Maggiore, who was HIV positive, had refused to take medications that would have reduced the risk of transmission to her unborn child, and also declined to have her tested for HIV once she was born. Maggiore disputed the coroner’s report, and insisted that her daughter had in fact died from an allergic reaction to antibiotics. All of these details were echoed in the ostensibly-fictional TV show.

During the interview, Dr. Dee is initially unaware of Maggiore’s background, and of the final shape of the programme for which she had been an adviser; she explains that she found the show too difficult to watch because the subject matter was so close to the situations she saw every day through her work with HIV-positive people. When Maggiore finally reveals the full facts, Dee seems shocked yet sympathetic.

To hear Maggiore calmly recount the details of a programme so obviously based on her own life is chilling enough. But the most painful moment comes when she ridicules the fact that, in the fictionalised version of her life, the story ends with the denialist mother dying suddenly from an AIDS-related illness. Maggiore wonders aloud whether this might have been some kind of ‘wish fulfilment’ on the part of those who despise her refusal to accept the conventional view of HIV and AIDS.

Throughout the programme Maggiore seems lucid and eloquent. She was clearly a highly intelligent person who believed passionately that she was doing the right thing – which of course made her all the more dangerous. I’m not sure I’ve ever seen a starker illustration of how far a well-structured, well-intentioned, well-expressed, and internally consistent argument can take you, even when your basic facts are nonetheless catastrophically flawed. Tragically there are some facts that no amount of nuanced, intelligent argument can refute, or psychoanalyse away.

See also: The parallels between AIDS denial and Holocaust negationism

“Children must never play with matches”: Ophelia Benson on the folly of amateur medicine

It’s good to question conventional wisdom, except when it isn’t. Conventional wisdom holds that a bridge designed by engineers and built by reputable builders is safer to drive across than one designed by shamans and built by hairdressers. Questioning that conventional wisdom is not really all that productive, and if anyone listens to the questioning, it’s downright lethal.

So with Christine Maggiore.

Until the end, Christine Maggiore remained defiant.On national television and in a blistering book, she denounced research showing that HIV causes AIDS. She refused to take medications to treat her own virus. She gave birth to two children and breast fed them, denying any risk to their health. And when her 3-year-old child, Eliza Jane, died of what the coroner determined to be AIDS-related pneumonia, she protested the findings and sued the county.

That’s the risky kind of questioning conventional wisdom – and it risks other people as well as oneself. That’s why Prince Charles makes me angry when he indulges his passion for denouncing non-alternative medicine, and it’s why Juliet Stevenson made me angry when she used her celebrity to denounce the conventional wisdom about the MMR vaccine and autism, and it’s why Christine Maggiore makes me angry even though she’s now dead. It makes me angry that she breast-fed her children and it makes me angry that she went on television to denounce research showing that HIV causes AIDS. People shouldn’t do that. People shouldn’t take on life and death medical issues when they have no training or expertise in the subject. People shouldn’t trust their own judgment that completely.

For years, the South African government joined with Maggiore in denying that HIV is responsible for AIDS and resisting antiretroviral treatment. According to a new analysis by a group of Harvard public health researchers, 330,000 people died as a consequence of the government’s denial and 35,000 babies were born with the disease.

It’s not a subject for hobbyists or cranks or princes or actors. Children must never play with matches.

See also: The parallels between AIDS denial and Holocaust negationism

David Gorski on the insidious myth of “balance” in science reporting

I believe that most reporters in the media do really want to get it right. However, they are hobbled by three things. First, many, if not most, of them have little training in science or the scientific method and are not particularly valued by their employers. For example, witness how CNN shut down their science division. Second, the only medical or science stories that seem to be valued are one of three types. The first type is the new breakthrough, the cool new discovery that might result in a new treatment or cure. Of course, this type doesn’t distinguish between science-based and non-science-based “breakthroughs.” They are both treated equally, which is why “alternative medicine” stories are so popular. The second type is the human interest story, which is inherently interesting to readers, listeners, or viewers because, well, it’s full of human interest. This sort of story involves the child fighting against long odds to get a needed transplant, for example, especially if the insurance company is refusing to pay for it. The third type, unfortunately, often coopts the second type and, to a lesser extent, the first type. I’m referring to the “medical controversy” story. Unfortunately, the “controversy” is usually more of a manufactroversy. In other words, it’s a fake controversy. No scientific controversy exists, but ideologues desperately try to make it appear as though a real scientific controversy exists. Non-medical examples include creationism versus evolution and the “9/11 Truth” movement versus history. Medical examples include the so-called “complementary and alternative medicine” movement versus science-based medicine and, of course, the anti-vaccine movement.

AIDS sceptic Celia Farber on the death of Christine Maggiore

From Dean’s World

The news has been shattering to all who loved her around the world. Speaking for myself, I can say that Christine Maggiore was one of the strongest, most ethical, compassionate, intelligent, brave, funny, and decent human beings I have ever had the honor to know. I spoke to her in great depth about all aspects of life, death, love, and this battle we both found ourselves mired in, and I will be writing about her and about those conversations here, in the future. No matter what she was going through, and it was always, frankly, sheer hell–every day of her life, since 2005, she faced, acute grief, sadistic persecution, wild injustice, relentless battle, and deep betrayal–she was always there for her friends, and she never descended to human ugliness. She always tried to take the high road. She always tried to be stronger than any human being could ever be asked to be. I feared for her life, always. I feared the battle would kill her, as I have felt it could kill me, if I couldn’t find enough beauty to offset the malevolence. This is a deeply occult battle, and Christine got caught in its darkest shadows.

She had apparently been on a radical cleansing and detox regimen that had sickened her and left her very weak, dehydrated, and unable to breathe. She was shortly thereafter diagnosed with pneumonia and placed on IV antibiotics and rehydration. But she didn’t make it.

Those who loved her, as I did, have our own interpretations of what ultimately killed her–a combination of unrelenting heartbreak and the effect of being subject to a constant, unrelenting media driven hate campaign, despite the complete legal clearing of her name in the death of her daughter Eliza Jane in 2005, who died after taking an antibiotic, and whose cause of death has been tortuously debated. Christine and her husband Robin were denied the right to adopt a child, or foster a child, due to a single article in the L.A. Times which cast her as a murderer.