The Parliamentary Question Carter Ruck and Trafigura don’t want you to see

Update 19/10/09 – London art gallery dumps toxic sponsorship deal with Trafigura!

From The Guardian

The Guardian has been prevented from reporting parliamentary proceedings on legal grounds which appear to call into question privileges guaranteeing free speech established under the 1688 Bill of Rights.

Today’s published Commons order papers contain a question to be answered by a minister later this week. The Guardian is prevented from identifying the MP who has asked the question, what the question is, which minister might answer it, or where the question is to be found.

The Guardian is also forbidden from telling its readers why the paper is prevented – for the first time in memory – from reporting parliament. Legal obstacles, which cannot be identified, involve proceedings, which cannot be mentioned, on behalf of a client who must remain secret.

The only fact the Guardian can report is that the case involves the London solicitors Carter-Ruck, who specialise in suing the media for clients, who include individuals or global corporations.

From Parliament.uk, “Questions for Oral or Written Answer beginning on Tuesday 13 October 2009”

(292409)

61

N Paul Farrelly (Newcastle-under-Lyme): To ask the Secretary of State for Justice, what assessment he has made of the effectiveness of legislation to protect (a) whistleblowers and (b) press freedom following the injunctions obtained in the High Court by (i) Barclays and Freshfields solicitors on 19 March 2009 on the publication of internal Barclays reports documenting alleged tax avoidance schemes and (ii) Trafigura and Carter-Ruck solicitors on 11 September 2009 on the publication of the Minton report on the alleged dumping of toxic waste in the Ivory Coast, commissioned by Trafigura.

Click here for more background on the Trafigura/Carter-Ruck libel-abuse cover-up

UPDATE – pleased to see that the mighty Guido Fawkes had the same idea. Injunction scuppered…

UPDATE 2 – “Jack of Kent” gives a legal view

UPDATE 3 – Big thumbs up to The Spectator for, I think, being the first mainstream UK media to break ranks and fully report what’s been going on. If only they were this good the whole time – for any Spectator staff who are reading, can I request more of the defending-democracy stuff and less of the pseudo-debating AIDS-denialism? I hope Lord Fowler knows what you’re letting him in for!

Yet more false and misleading claims on asbestos from the Sunday Telegraph

The Sunday Telegraph’s latest comment piece from Christopher Booker, downplaying the health risks of white asbestos, is in a similar vein to the 41 other articles that Booker has had published on the subject since 2002.

Booker again repeats his false (and dangerous) claim that white asbestos poses “virtually zero” risk to human health, and his long-debunked assertion that the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) once agreed with him on this point.

He claims that concerns about the health risks of white asbestos are based on a “confusion”, which has been “deliberately promoted” by personal injury lawyers and asbestos removal contractors, and that the Health and Safety Executive has latterly been “shamefully conniving with both these rackets”.

The ‘hook’ for the latest article is a ruling from the Advertising Standards Agency, about a series of HSE radio ads highlighting the risks faced by construction and maintenance workers in older buildings where asbestos is still be present. The ads were part of a wider HSE campaign to encourage trades-people to protect themselves adequately when handling asbestos.

Following a complaint from the indefatigable John Bridle, the Advertising Standards Agency had ruled that the advertisements were misleading.

The HSE had suggested that six joiners, six electricians, three plumbers and 20 tradesmen died every week from asbestos-related diseases. After looking at the calculations used to produce these figures, the ASA concluded that the numbers used should instead have been “six joiners, five electricians, three plumbers and 18 other tradesmen” (ie. a total of 32 workman dying each week from asbestos-related illness rather than 35).

The ASA agreed that “it was reasonable for HSE to highlight the death rates for asbestos-related diseases, including those which were based on estimates, to today’s tradesmen. We considered however that the ads should have made clear that they were based on estimates and the claims should have been made in less absolute tones.”

Booker says that Bridle had complained to the ASA that the HSE’s publicity campaign was “wilfully misleading”, and that their estimates about the number of asbestos deaths was “wildly exaggerated”, and that the ASA had upheld all of Bridle’s complaints.

But so far as I can see, the ASA ruling did not conclude the HSE had deliberately set out to mislead people, or that the figures they used were “wildly exaggerated”. And there is certainly nothing in the ruling to support Booker’s conspiracy theory that the Health and Safety Executive had been “putting out advertisements designed to panic the public into falling for the wiles either of the lawyers or of rapacious removal contractors.”

“Don’t Get Fooled Again” at Leicester Skeptics in the Pub

I had an excellent time on Tuesday talking about state-sponsored conspiracy theories to Leicester “Skeptics in the Pub”. The event was masterfully-convened by Simon Perry, who also happens to be one of the chief authors of the “quacklash” against the General Chiropractic Council’s misguided and heavy-handed abuse of UK libel law to attack freedom of speech. Also in attendance was the legendary Neil Denny, of “Little Atoms” fame.

In less than two years, Leicester skeptics have come from nowhere to being able to draw a crowd of 100 people on a Tuesday night on a regular basis. There were some interesting chats afterwards, and it was also great to meet James, Andy and Al. Unfortunately the feed to the Ipadio phonecast didn’t work 100% on this occasion, but it’s nothing that couldn’t be fixed and does like a great idea for future events.

Leicester Skeptics in the Pub

All being well, my talk to Leicester Skeptics in the Pub this evening should be coming through live online from 7.30pm via this link: http://ipadio.com/phlogs/RichardWilson/

This of course is in no way a substitute for the real-life, actual, 3-dimensional Leicester Skeptics experience, but if you can’t make it this could be a good second. If for any reason what comes out of your PC speakers is anything less than a virtuosi performance, this will doubtless be wholly due to interwebs interference and you should really have come along to the real thing!

Recommended reading

If you liked “Don’t Get Fooled Again”, then you may also like (or find interesting):

Mistakes Were Made But Not By Me, Carol Tavris and Elliot Aronson

A Mind of Its Own: How your brain distorts and deceives, Cordelia Fine

The Cigarette Century, Allan M Brandt

Flat Earth News, Nick Davies

Mortal Questions, Thomas Nagel

How Mumbo-Jumbo Conquered The World, Francis Wheen

In Defence of History, Richard J Evans

Denying Aids, Seth Kalichman

Mortal Combat: AIDS Denialism and the struggle for anti-retrovirals in South Africa, Nicoli Nattrass

Bad Science, Ben Goldacre

Trick or Treatment?, Simon Singh and Edzard Ernst

Second Front, John R Macarthur

Toxic Sludge is Good For You, John Stauber and Sheldon Rampton

In Retrospect, Robert S McNamara

King Leopold’s Ghost, Adam Hochschild

Status Anxiety, Alain de Botton

Real England, Paul Kingsnorth

Counterknowledge, Damian Thompson

Mysticism and Logic, Bertrand Russell (free e-book version available here)

Radical then, Radical Now, Jonathan Sacks

The God Delusion, Richard Dawkins

Charity commission says it has no powers to act against a UK charity putting out dangerous misinformation on AIDS

I recently blogged about a UK registered charity called the “Immunity Resource Foundation”, whose official objectives include:

“To advance the education of the public in the fields of medicine, health care and medical science”

and

“To relieve sickness and assist sick and disabled persons… by providing them with access to information concerning diseases and medical conditions (and in particular AIDS)…”

But the information promoted on the charity’s website includes the claim that “the AIDS edifice is built upon a false hypothesis”, that AIDS “is not an infectious disease” and that “HIV cannot cause AIDS”. The charity also provides links to a range of AIDS denialist websites, including “Living Without HIV Drugs” – which urges HIV-positive patients to stop taking conventional medications.

As has been well-documented elsewhere, this kind of misinformation around HIV and AIDS has already done enormous damage, with a grim roster of HIV-positive AIDS denialists dying after refusing to take medicines that could have saved their lives, and many thousands more deaths resulting from the application of AIDS denialist ideas by the South African government.

Far from advancing the “education of the public”, any organisation which promotes these ideas is disseminating dangerous misinformation. And far from relieving sickness, the promotion of AIDS denialism under the guise of providing health information can have deadly consequences.

The Charity Commission exists to ensure that charities registered in England and Wales benefit the public interest and act in accordance with their stated objectives. However, when contacted about the activities of the Immunity Resource Foundation, the Commission stated that:

We do not have the remit or expertise to judge whether they are providing the correct advice. We can only become involved in matters where our regulatory powers permit us to intervene and unfortunately this issue falls outside of that remit.

The upshot of this seems to be that a registered charity is free to make false, misleading and dangerous scientific claims about a major public health issue – even where this runs directly contrary to the charity’s official objectives – because the government body that regulates charities does not have access to the technical expertise necessary to evaluate such claims.

This seems like quite a big loophole, and also something of a double-standard. Whereas a private business that makes false scientific claims about its products is answerable, at least in principle, to the Trading Standards Institute, it would appear that UK registered charities are currently free to disseminate pseudo-science more or less with impunity.

Climate change “scepticism” and Spiked Online

Spiked Online‘s Rob Lyons seems (understandably, I guess) riled by my recent comments on this blog about his magazine’s editorial record, and in response has published an impressively-detailed critique of “Don’t Get Fooled Again”.

While I’m not sure Rob really addressed the points I made about Spiked, he does have some interesting things to say about DGFA, taking me to task for (among other things) more or less ignoring the viewpoint sometimes described as “climate change scepticism”.

Actually it does get a mention in the book, but Rob could be forgiven for missing it, as the mention is very brief (p84), taking up marginally less space than I give to the self-described “sceptics” about Darwin’s theory of evolution.

Though it seems undeniable that the climate change doubters have had a major cultural and political impact, I’m just not convinced that in scientific terms their views are any more significant than those of the people who believe that MMR causes autism, or that homeopathy can cure cancer, or that the moon landings never happened, all of whom also get ignored in the book.

While I do have my own views about climate change “scepticism” (some of which have made their way onto this blog, and some of which I allude to here), and while I do think that there are some easy inferences we can draw based on other examples given in “Don’t Get Fooled Again” (perhaps especially AIDS denialism), I also feel that the subject’s already been very well covered elsewhere (eg. here), and wanted to concentrate on some issues that hadn’t had such a wide airing.

Rob’s criticisms go a fair bit wider than that, and given the emphasis that the book places on debate and discussion, I wish I had a bit more time to respond properly, but I guess this will have to do for the moment…

*Update* – One other key criticism Rob makes is that the book exaggerates the success of the PR firm Hill and Knowlton in defending the image of the tobacco industry during the 1960s and 1970s. He cites figures from the American Cancer Society which show that smoking rates among both adult males and females in the US, UK and Japan actually fell quite steadily from 1960 onwards. Adults are defined as over 18 in the US, over 16 in the UK, and over 20 in Japan.

This is a fair point, but I’m not sure it gets H&K off the hook. For the US at least (H&K’s home market, and the case study I focus on in the book), while there was a decline in the percentage of adults who smoked, the actual number of cigarettes sold each year continued to grow until the mid 1970s, (see p227 of Allan M Brandt‘s “The Cigarette Century”) – and lung cancer cases only began declining in 1995. Whether this was because the industry was managing to sell more cigarettes, year on year, to the minority of adults who continued to smoke, or because another group of potential smokers not included in the ACS figures – children, began to play a more important role in the market, or because of some combination of factors, the continued rise in sales for more than two decades after the link between smoking and cancer was first proven suggests that the Hill and Knowlton PR strategy was hardly a commercial disaster.

What Rob doesn’t do, so far as I can see, is clarify the nature of Spiked’s own relationship with Hill and Knowlton, as discussed here.

Spiked Online give their verdict on “Don’t Get Fooled Again”

From Spiked Online

Question everything — even environmentalism

A new book on the importance of being sceptical about received wisdom and simplistic spindoctoring mysteriously leaves out one area of life where scepticism is thoroughly frowned on today: climate change.

by Rob Lyons

When Karl Marx was asked by his daughter to fill in a ‘confession’, a light-hearted Victorian questionnaire, he declared that his favourite motto – usually attributed to Rene Descartes – was De omnibus dubitandum. Or, to put it another way, ‘question everything’.

These are wise words. Any serious inquiry into the truth should start with this pithy formulation of scepticism in mind. So when Richard Wilson’s book Don’t Get Fooled Again: The Sceptic’s Guide to Life arrived in the spiked office a few months back, I was looking forward to an illuminating exploration of the role of scepticism today.

Yet while there are some sensible restatements of the basic principles that should steer readers through the modern world, Wilson’s guide seems a little trite. It’s the kind of book that might be an entertaining read for a student heading off to university rather than a sage treatment of an important idea. Judging from the book itself and Wilson’s writings elsewhere, it seems he is unwilling to follow through on the logic of his pro-sceptical approach when it comes to the central issues of our day.

Don’t Get Fooled Again begins with a health warning: people are inclined by nature to a little self-delusion. The average person, Wilson advises, tends to believe that they are above average. Only depressives, it seems, have a realistic assessment of their own worth. This is harmless enough, he argues, as optimistic and self-confident people tend to do better in life. However, this propensity to believe what is convenient is positively dangerous when it comes to wider social issues. From public-relations spin to psuedoscience, Wilson relates numerous instances in which our capacity to swallow a lie has had negative, even deadly consequences. We need to keep our wits about us.

Wilson believes that ‘the basis of scepticism is essentially common sense… to be sceptical is to look closely at the evidence for a particular belief or idea, and to check for things that don’t add up’. He adds: ‘This is not the same thing as being a cynic. Cynics like to assume the worst of people and things. Sceptics try to make as few assumptions as possible.’

He also notes that the mainstream media is a flawed resource in a number of ways, from the way stories are selected as newsworthy to the way PR companies and other interest groups manipulate what is presented. Wilson praises the internet as a means by which we can find the primary sources of information for ourselves and question what is being presented to us as the truth. ‘Just as you shouldn’t believe everything you read in the papers’, he writes, ‘neither should you assume, a priori, that everything that isn’t in the papers isn’t true’.

His first major example is the work of giant public relations agency, Hill & Knowlton (H&K). The firm has been involved in a number of controversial examples of spin. In October 1990, as Wilson reminds us, a 15-year-old Kuwaiti girl, ‘Nurse Nayirah’, claimed that Iraqi soldiers had stolen incubators from a hospital in Kuwait City, leaving the children that were in them to die. The claim was that more than 300 children had perished as a result. In fact, ‘Nurse Nayirah’ was the daughter of the Kuwaiti ambassador to the US who had been coached to tell this tale by staff at H&K.

If that lie led to the first war against Iraq, Wilson argues that H&K’s past crimes were even worse, leading to the deaths of millions of people. In the 1950s, the agency was hired by tobacco manufacturers to deal with the threat from the emerging medical evidence linking smoking with lung cancer.

H&K’s response was obfuscation: try to convince the public that the link was unproven and that there was genuine controversy, when the link was, in fact, well established. To this end, the firm promoted Clarence Cook Little, an American geneticist, as a leading expert on cigarettes and ill-health when he was nothing of the kind, while creating a Tobacco Industry Research Committee (TIRC) to create the impression that the industry was actively investigating the link. In truth, the TIRC was little more than a PR operation. By 1964, a US government report had confirmed the link but, according to Wilson, H&K’s strategy was so successful that cigarette sales continued to rise before peaking a decade later.

As it happens, Wilson overstates H&K’s success in this matter. As figures from the American Cancer Society note, smoking rates in the USA, UK and Japan were falling before 1964 and have carried on falling ever since (1). Not only that, but the exposure of the tobacco industry’s attempts to downplay the dangers of cigarettes now mean that nothing that any tobacco company ever says is believed, leaving the industry completely unable to make any meaningful intervention on the debate on passive smoking, for example, and tainting anyone who has ever had anything to do with ‘Big Tobacco’. That sounds more like an object lesson in how not to conduct a PR campaign.

Wilson goes on to discuss a variety of other ways in which a failure to examine the evidence and thus fall victim to wishful thinking and ‘groupthink’ has led to disaster. One such example is the pseudoscience of Trofim Lysenko, the ‘barefoot scientist’ whose ideologically agreeable ideas about agriculture and rejection of Mendelian genetics helped place him at the forefront of Soviet science for decades, while leading to crop failures and malnutrition.

Wilson puts much of the blame for the mass starvation of the Great Leap Forward in China from 1958 to 1961 – which claimed 30million lives – on the barmy ideas promoted by Lysenko and adopted by Mao. Again, Wilson almost certainly overstates his case. While Soviet ideas certainly inspired the Chinese regime, the obsession with collectivisation and meeting pointless, centrally decreed targets had more of an impact than the losses incurred due to Lysenko’s dubious methods.

Another tragedy was the rise of AIDS denialism in the 1980s and 1990s. The widely accepted theory that AIDS is caused by a virus, HIV, was rejected both by some researchers – most notably by a high-profile American virologist, Peter Duesberg – and by AIDS activists who were mistrustful of the medical establishment. Retroviral therapies, such as AZT, were regarded as poisons and some even suggested that it was these drugs, not HIV, that were responsible for disease. Sadly, the leading activist proponents of this view died one by one, refusing the treatment that could have saved their lives.

The influence of this denialism was particularly strong in South Africa, a country greatly afflicted by the spread of AIDS. Around the turn of the century, the then-president Thabo Mbeki and his ANC government did everything in their power to delay the widespread use of retrovirals, leading to many unnecessary deaths. The lesson is that once an irrational idea gets a grip in the corridors of power, the consequences can be devastating.

On the other hand, the South African government were not alone in promoting irrational ideas. The British government was happy to use AIDS to try to promote a conservative sexual morality in a politically correct guise, providing a template for health-based scaremongering that continues to this day. While thousands of people in quite specific groups were dying of a new and terrible illness that demanded an all-out research effort to resolve, millions of pounds were being wasted on pointless scare campaigns aimed at everyone. Surely a true sceptic would interrogate these mainstream ideas to reveal the agendas of those promoting them?

In his final chapter, Wilson sums up the main elements of his sceptical outlook. Fundamentalism – the assertion of the ‘absolute literal truth of a particular set of beliefs’ – and relativism – the belief that any view can be true – are, in Wilson’s view, very similar and both are to be avoided since they immunise believers to logic and truth. Wilson also warns against conspiracy theories, pseudo-scholarship (a bogus agenda dressed up as a serious assessment of current knowledge), and pseudo-news (fraud or spin presented as truth).

He also returns to his earlier concerns about wishful thinking and warns against the way debates can be conducted by ‘over-idealising’ the outlook of one’s own side while ‘demonising perceived enemies’, with the upshot being the ‘moral exclusion’ of one side and ‘groupthink’, where ‘doubters and dissenters are stereotyped as weak, disloyal or ill-intentioned’.

This is all sound advice. Yet what is most surprising, given that Wilson’s book is a discussion of scepticism, is that he avoids the one area in which sceptics are most prominent today: climate change. There are plenty of high-profile advocates for action around manmade greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions who exhibit all the dubious behaviour that Wilson rightly criticises elsewhere. Yet Wilson is silent on the matter.

There is little dissent on the idea that the world has got warmer in the past 100 years or so. Nor is there any serious dissent that carbon dioxide is a greenhouse gas which will tend to make the world warmer as levels of it increase in the atmosphere. And there’s certainly no doubt that human beings have caused the release of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere from industry, transport and agriculture. If economic development continues in its current manner then, all other things being equal, we would expect the Earth’s temperature to rise.

Just how much warmer the world is likely to get is still unknown. What we have is a range of best guesses made on the basis of an incomplete temperature record, computer models that still have some way to go in accurately representing our climate, and genuine and important uncertainties in the basic physics of climate change. So while a warming world is our best available working assumption, how much the world’s temperature may change in the future is still a legitimate subject of scientific inquiry. Quite aside from the complexities of atmospheric physics, there are wider questions to be answered about the consequences of such warming and what the best policy response would be.

Yet the public discussion of climate change often obliterates such subtleties. The science of global warming is not presented as a series of provisional conclusions that must be revised as new evidence arises – which would be a properly sceptical approach following the argument in Don’t Get Fooled Again – but as ‘The Science’, a catechism of received truths that brooks no opposition. Frequently, a moral and political argument about the evils of humanity and industrial society is represented as a set of incontrovertible scientific facts.

Those who seek to question any aspect of this catechism are treated in precisely the terms Wilson warns against. James Hansen, the NASA scientist who has been closely identified with promoting the need for action on climate change, suggested to a US congressional committee in June 2008 that the leaders of the oil and coal industries would be ‘guilty of crimes against humanity and nature’ if they don’t change their ways. In An Inconvenient Truth, Al Gore derided those who don’t agree with him by questioning their rationality, stating that those who believe that the Moon landings were faked or who think the Earth is flat should ‘get together with the global warming deniers on a Saturday night and party’. Indeed, the very use of the term ‘denier’ to describe a critic of climate change science or policy has very conscious and pointed parallels with Holocaust denial.

Even scientists who firmly argue that the mainstream scientific position is correct, but who have been concerned about some of the alarmist statements made in science’s name, have been criticised as weak, disloyal or ill-intentioned.

Wilson has nothing to say in his book on these things. Yet on his website, he specifically criticises spiked for taking the kind of sceptical approach to the politics of environmentalism that he encourages people to adopt in relation to various other issues (2). Wilson engages in the kind of smearing rhetoric he criticises in other situations, making the defamatory and utterly false suggestion that spiked could only say such ‘pro-corporate’ things because it is paid to do so. He only tolerates a certain kind of scepticism, it seems, the kind that doesn’t question any of the apparently inconvertible truths held by him and other eco-enlightened individuals.

Sadly, Wilson’s own definition of cynics – those who ‘assume the worst of people and things’ – seems all too apt a description of his own outlook.

Rob Lyons is deputy editor of spiked.

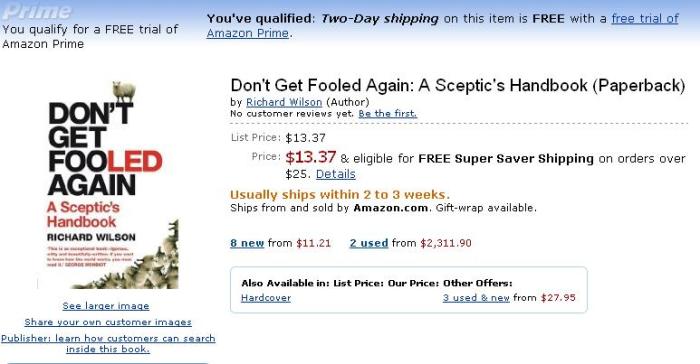

Don’t Get Fooled Again: A Sceptic’s Guide to Life, by Richard Wilson, is published by Icon Books. (Buy this book from Amazon(UK).)

(1) The American Cancer Society’s Tobacco Atlas suggests that adult male smoking rates in the USA fell from 51 per cent in 1960 to 44 per cent in 1970 and 38 per cent in 1979, with similar falls in the UK and Japan. These declines are also mirrored for female smokers. H&K clearly weren’t that successful.

(2) Spiked Online: the rohypnol of online news and comment, Don’t Be Fooled Again blog

UK registered charity is an AIDS denial front group

The Immunity Resource Foundation (UK charity 1105986) says that its aims include:

“(I) TO ADVANCE THE EDUCATION OF THE PUBLIC IN THE FIELDS OF MEDICINE, HEALTH CARE AND MEDICAL SCIENCE; AND

(II) TO RELIEVE SICKNESS AND ASSIST SICK AND DISABLED PERSONS …BY PROVIDING THEM WITH ACCESS TO INFORMATION CONCERNING DISEASES AND MEDICAL CONDITIONS (AND IN PARTICULAR AIDS) AND THE TREATMENTS, THERAPIES AND RESEARCH STUDIES RELATING THERETO, AND WITH ADVICE AND SUPPORT;”

But the scientific claims about AIDS published on the organisation’s website are dangerously inaccurate. On this page, Joan Shenton, the organisation’s “Founder and administrator”, suggests that AIDS “is not an infectious disease” and that “HIV cannot cause AIDS”.

The articles linked to on this page all lean in the same direction, and many of them are by known AIDS denialists, notably the discredited virologist Peter Duesberg and the journalists Neville Hodgkinson, Celia Farber and John Lauritsen.

A Harvard study published last year concluded that the adoption of AIDS denial in South Africa by the government of Thabo Mbeki in the early part of this decade had contributed to more than 365,000 preventable deaths. In a speech in 1999, Mbeki had cited “the huge volume of literature on this matter available on the Internet” in support of his position on HIV and AIDS.

Review: “Mistakes Were Made (But Not By Me)” by Carol Tavris and Elliot Aronson

I’m just back from a very relaxing break in which I re-read the absolutely outstanding book “Mistakes Were Made (But Not By Me)” by psychologists Carol Tavris and Elliot Aronson. It has the rare merit of being accessible, well-written, solidly backed-up and jaw-droppingly interesting, all at the same time.

Elliot Aronson was one of the leading pioneers of cognitive dissonance theory, which holds that a prime motivation for human beings in forming new ideas is to justify and defend our pre-existing beliefs, even where this means torturing logic and evidence to breaking point. This, in turn, very often entails (more dangerously) justifying at all costs the decisions we have previously taken, more or less regardless of whether those decisions were right. Dissonance theory predicts that, in general, the more serious and irrevocable a particular decision is, the harder we will work to defend it – and (more dangerously still) to dismiss any evidence that the decision may have been a really bad one. Most dangerously of all, our need to defend a bad decision made on the basis of a flawed principle may lead us into making yet more bad decisions in future: The cost of giving up our flawed principle, and choosing a different path next time, would be to admit that we were wrong and accept responsibility for the damage done by our initial mistake. For most human beings this is an incredibly difficult thing to do. So instead we stick to our guns, and compound our flawed decision with further flawed decisions, regardless of all evidence.

There’s some particularly compelling stuff in the book about the damage done by Freudian pseudo-psychology in the 80s and 90s, when dozens of people were falsely imprisoned on the say-so of psychologists who believed in the now almost wholly discredited notion that child abuse victims would routinely repress and forget traumatic memories, which could later be recovered by hypnosis. In fact, according to Tavris and Aronson there is no reliable evidence that traumatic memories are repressed in this way – if anything, traumatic memories tend to be so clear and intense that the victim is regularly and painfully reminded of them even when they’d rather not be. Worse still, there is strong evidence that hypnosis and the use of leading questions can lead to the creation of ‘memories’ that, whilst compelling and ‘true’ to the person experiencing them, are wholly false. The authors recount a litany of cases where parents and teachers were imprisoned solely on the basis of such ‘recovered’ memories, only later to be exonerated after evidence emerged of just how flawed and unscientific the methods of ‘recovered memory’ specialists actually were.

I found this account especially striking for two reasons: Firstly, I was not aware of just how weak the evidential basis is for so many of the Freudian concepts – like ‘repression’ – which still hold such sway within our culture. Secondly, and more tragically, Tavris and Aronson show how, just as dissonance theory would predict, many of the leading lights of the ‘recovered memory’ movement – including some of those who were later found guilty of professional misconduct for their flawed testimony in court cases – continue to insist that they were right all along. To do otherwise would be to admit to themselves that their incompetence helped imprison dozens of innocent people, and tear apart countless families.

One of the most disconcerting implications of the book is, of course, that dissonance theory applies to all of us, and nobody is immune – the authors give a couple of examples from their own lives to drive this point home. But the good news is that by becoming more aware of our enormous drive towards self-justification, we can – at least on occasions – catch ourselves before we’ve gone too far, and try to steer ourselves back to reality.

A key point that emerged for me – and this is something that I’ve really seen a lot of since I began researching “Don’t Get Fooled Again” – is the extent to which so many of the most dangerous delusions seem to revolve around an over-attachment to our own egos. The quacks and cranks who desperately need to convince the world that they possess a special, earth-shattering insight that the scientific community has somehow missed – or is conspiring to suppress. The corporate executives who have persuaded each other that their cleverly-rebranded variation on the age-old “Ponzi scheme” is in fact a revolutionary “new paradigm” to which the basic laws of economics simply do not apply. The conspiracy theorists who believe that they uniquely can see through the ‘official story’ that everyone else is too stupid or cowardly to question. The antidote, it seems to me, may have something to do with re-emphasising one of the key elements of scepticism (albeit one that often seems to get forgotten) – intellectual humility:

Having a consciousness of the limits of one’s knowledge, including a sensitivity to circumstances in which one’s native egocentrism is likely to function self-deceptively; sensitivity to bias, prejudice and limitations of one’s viewpoint. Intellectual humility depends on recognizing that one should not claim more than one actually knows. It does not imply spinelessness or submissiveness. It implies the lack of intellectual pretentiousness, boastfulness, or conceit, combined with insight into the logical foundations, or lack of such foundations, of one’s beliefs.

This, of course, is easier said than done…

Spiked Online – The rohypnol of web-based news and comment

*See also my response to Rob Lyons: Climate change “scepticism” and Spiked Online*

Naomi and Gimpy have written a couple of good things today about the arch-libertarians over at Spiked Online. Spiked is an odd phenomenon, founded a few years ago by a group of ex-members of the “Revolutionary Communist Party”. Despite adopting many of the trappings of the left, Spiked takes a staunchly pro-corporate/pro-authoritarian-government line on a wide range of issues, including climate change, breastfeeding, smoking, obesity, gun control, human rights in China, corruption in Africa, and international justice.

On climate change, the position seems to swing between a) the standard denialist belief that global warming is a self-hating, anti-working-class, group fantasy (or perhaps even a conspiracy) among lefty bourgeois enviro-scientists and b) the slightly more nuanced, if no less bewildering, line that yes, maybe something is happening to the climate, and yes, maybe scientists are predicting that millions of people will die because of it, but science alone cannot tell us whether or not this is a bad thing.

As seems pretty clear in the two articles picked apart by Naomi and Gimpy, the arguments on Spiked are often so tortured that it’s difficult to believe that the author genuinely holds to what they’re saying.

Which of course begs the question why… Contrarianism clearly seems to be a part of it. As I learned at my sisters’ expense when I was growing up, disagreeing with other people for the sake of it can be both fun and entertaining, especially when you can see that people are getting really annoyed by it – and Spiked clearly do have a talent for winding everyone up.

But while Spiked’s editor, Brendan O’ Neill, often makes light of claims that he and his outfit take ‘cash for copy’, it’s difficult to ignore the galaxy of corporates listed as associates on page 10 of the Spiked Online “Brand Manager’s pack”.These include Bloomberg, BT, Cadbury Schweppes, the PR firm Hill and Knowlton, IBM, INFORM (“INFORM is an IDFA initiative set up on behalf of UK infant formula manufacturers, namely SMA Nutrition, Cow & Gate, Milupa and Farley/Heinz…”), the International Policy Network (a corporate lobby group funded by the Exxon oil company among others), Luther Pendragon (another PR firm), the Mobile Operators Association, Orange, O2, Pfizer, and the Society of Chemical Industry.

Hill and Knowlton in particular stand out because of their unparalleled, 50-year track record in creating and disseminating pro-corporate disinformation using cutting-edge PR techniques. During the 1950s, as recounted in “Don’t Get Fooled Again”, H&K pioneered the concept of “manufactured controversy” to defend the tobacco industry, muddying the water around the link between smoking and cancer, and successfully staving off regulation, long after a clear consensus had emerged among scientists.

During the 1990s, H&K cleverly exploited the technique of “Astroturfing” – creating a fake ‘grassroots’ organisation – to set up “Citizens for a Free Kuwait”, a group covertly funded by the Kuwaiti government, to campaign for US intervention following the Iraqi invasion in 1990. H&K famously coached a 14-year-old Kuwaiti girl, “Nurse Nayirah”, before an appearance in Congress in which she claimed to have seen Iraqi soldiers looting incubators from a Kuwaiti hospital, and leaving babies “to die on the cold stone floor”. It only emerged later that Nayirah was the daughter of Kuwait’s Ambassador to the United States, and that she had never worked at the hospital. The incident she described was never substantiated – but her testimony has been credited with swinging Congressional support in favour of war at a time when opinion was still wavering.

H&K also represented the Chinese authorities after the Tiananmen Square massacre, and the Indonesian government during their notorious occupation of East Timor. In the early 1990s, an un-named H&K executive was quoted as saying that “we’d represent Satan if he paid”.

Sourcewatch report that over half of Spiked Online’s public events in recent years have been held at H&K’s London offices.

Over-used expressions part I – “Paradigm shift”…

A brief jaunt through Google News reveals over 500 “paradigm shifts” in the last three weeks, including:

“A Paradigm shift in Polymer material”, from ‘Materials Views’

A “Paradigm Shift in European Cash Clearing”, from Gerson Lehrman Group

Pakistan needing a “paradigm shift” to beat the Taliban, from the BBC

A “paradigm shift in how South Koreans view North Korea”, from the New York Times

… and Malaysia’s Social Security Organisation (SOCSO) simultaneously “working towards”, and “undergoing”, a major paradigm shift, from Bernama.com

Andrew Armour reviews “Don’t Get Fooled Again”

Andrew Armour’s very generous review picks up on some of the arguments I make in “Don’t Get Fooled Again” about marketing rhetoric – and in particular the seemingly ubiquitous idea that one new product or another constitutes a “new paradigm”. Armour has a professional marketing background, and witnessed first-hand the “dot com bubble” around the turn of the century:

From Andrew Armour’s Blog

I worked in e-commerce (print management and e-tail)… and remember well the presentations explaining how all retail was going to change, every shopping mall was going to die and banks would become mobile phone companies. I’m surprised we were not told that hover cars were to take us to the centre of the earth and the Mars colony would be open by 2012. Boo.com was going to be the biggest clothing retailer in the Universe, even though nobody really wanted to buy clothes on-line and it was making no money. The ‘old-rules’ did not apply. Marketing forces? Propositions? Mechanics? So, so passe. The smartest lesson I learned from all of this was that channels evolved and very seldom disappeared because alternatives come along. Radio and cinema did not replace theatre. TV did not replace movies and digital music will not replace the live concert. Printed media is the latest to be told it is going to die but I would bet that whilst it will evolve and change it will not go away. Then – Friends Reunited was going to change everything. Then Facebook. Then Twitter. And to be fair, maybe social media channels will change a lot, they will have a place in the mix and will evolve as another tool in the marketing box but let us not avoid critical thinking when listening to the high priests telling us social media will dominate the future…

Wilson points out that the ‘new paradigm’ has a strong cultural base that is often hard to counteract even with logic and evidence… to resist the notion that the new is always brilliant is to appear old, doomed, obsolete and conservative. But – how many new ideas that were championed and promoted passionately as the new paradigm were complete flops? Fascism or communism anyone? Boo.com? Friends Reunited? Balancing radical ideas with rational actions is the increasing challenge of marketers and with the proliferation of marketing channels and tools, it is the decision about what to communicate, to whom and how that will remain. As Kelly famously put it; ‘ In an endless world of abundance the only thing in short supply is human attention’.

Exclusive: Interview with Prof Seth Kalichman, author of “Denying Aids”

Professor Seth Kalichman’s excellent new book, Denying AIDS, is the most comprehensive account yet of the origins and development of a toxic ideology – AIDS denialism. In this e-interview, Seth discusses the book, and the urgent issues that it seeks to address.

RW: Why does AIDS denialism matter?

AIDS denialism matters because it kills people. I know this sounds like drama and hyperbole, but it is true. AIDS denialism creates confusion about the cause of AIDS. when people who need accurate information about HIV/AIDS are exposed to AIDS denialism they might actually believe that there is a debate among doctors and scientists about the cause of HIV when there is no such debate. AIDS denialists tell people that they should avoid HIV tests because they are invalid. In fact, HIV tests are extremely accurate and only rarely misdiagnose people with HIV. Being HIV infected and not knowing your HIV status means that you may not take measures to keep from spreading the virus. In many countries the majority of HIV infected people do not know they are infected. Huge resources are dedicated to getting people at risk for HIV tested. AIDS denialists undermine these efforts. Finally, AIDS denialism matters because it persuades people who have tested HIV positive to refuse HIV treatments. Denialists say that HIV treatments are toxic poison. In fact, HIV treatments are responsible for extending the lives and improving the health of people living with HIV/AIDS. In the US and UK, entire hospital wards that were once for AIDS patients are no longer needed. People with HIV are returning to work and living healthier lives because of treatments. AIDS deniers are trying to reverse this trend and return to days when there were no treatments.

RW: What was the inspiration for “Denying AIDS”?

I have been conducting HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment research in the US since 1989 and in South Africa since 2001. I have known for years that AIDS denialists exist, but like most people I thought that ignoring them would make them just go away. I also thought that very few people were AIDS denialists and that no one would listen to them. I suppose you could say I was denial about AIDS denialism. Like many others, I was very wrong about AIDS denialism. While working in South Africa I became aware of the devastating effects that AIDS denial was having in that country. The former President Thabo Mbeki had enlisted AIDS denialists among his advisors and bought into the idea that scientists are debating the cause of AIDS. Mbeki’s misguided AIDS policies resulted in over 330,000 senseless deaths and 35,000 babies who were needlessly infected with HIV. I was aware of the failure to offer treatment for South Africans living with HIV/AIDS and I knew that AIDS denial was to blame. In 2006 I also became aware of AIDS denialists in the US and UK. I received an email correspondence from someone I knew to be a well trained social psychologist in a teaching position at a respected university. She had written a very positive review of an old AIDS denialist book by Professor Peter Duesberg in California, the most notorious AIDS denialist. This psychologist had posted the book review at the RethinkingAIDS.com website. I was absolutely dumbfounded to learn that someone who I knew to be educated and who I believed to be intelligent had not only bought into AIDS denial but was actively propagating the myths. I started to look at the AIDS denialist literature and found it disturbing and also fascinating. I wanted to learn more about how seemingly intelligent people would come to believe absolute rubbish. So I decided to write Denying AIDS.

RW: What kinds of people become AIDS denialists, and what motivates them?

All kinds of people become AIDS denialists. Most visible are the fringe scientists because they write books and have websites. They are following in the footsteps of Peter Duesberg. Still, AIDS denialists who have academic positions do considerable harm because they create an impression of credibility. There are also rogue journalists who write about conspiracy theories and other sensational pseudo-news. AIDS denialist journalists do considerable harm because they bring AIDS denialism into the public eye. AIDS denialism also has its activists, typically people who have tested HIV positive and buy into denialism as a maladaptive coping strategy. These denialists also have credibility because they appear to be living healthy with HIV and not taking medications. There are even celebrities who support AIDS denialist activism, including the popular rock band the Foo Fighters and comedian Bill Maher. Tragically, AIDS denialist activists have infected their children and others and they themselves die of AIDS earlier than they may have if they accepted treatment. Then there is a large group of people who are prone to conspiracy theorizing, anti-government sentiments, and simply wanting to make mischief. These people are typically Internet bloggers with way too much time on their hands. Many seem not to realize the harm they are causing and most others just do not seem to care.

RW: Who are the key figures in the AIDS denial movement, and what are their ideas?

In my opinion, the key figures include the following people:

Peter Duesberg is the single most important figure in HIV/AIDS denialism because he is the only credentialed scientist who has worked with retroviruses, although not having worked with HIV, to propose that HIV does not cause AIDS. The rock star of AIDS denialism, he holds fast to his flawed ideas. What makes him unique is that he was once a respected scientist and now shows utter disrespect for science by refuting facts in the service of self-promotion.

David Rasnick is Peter Duesberg’s right hand man. Quite literally, in public Rasnick appears to be Duesberg’s personal assistant. At one time, he had a visiting scholar appointment with the Department of Molecular and Cell Biology at UC Berkeley (1996-2005), where he worked with Duesberg, although the university retracted his appointment. Rasnick is a conspiracy theorist, claiming that the US government propagates the ‘myth’ that HIV causes AIDS to allow the pharmaceutical industry. Rasnick served with Duesberg on the now infamous panel of AIDS experts and denialists convened by South African President Thabo Mbeki in 2000. In fact, Rasnick is credited, or blamed, with convincing Mbeki that there is a need for a scientific debate on the cause of AIDS. He also worked with Matthias Rath in conducting what are now ruled unlawful vitamin studies in South Africa.

Kary B. Mullis was a Nobel Laureate and is now among the who’s who of AIDS pseudoscientists. In 1994, Mullis co-authored the essay “What causes AIDS? It’s an open question” and he has appeared in several interviews in which he clearly questions whether HIV causes AIDS. Mullis said, “If there is evidence that HIV causes AIDS, there should be scientific documents which either singly or collectively demonstrate that fact, at least with a high probability. There is no such document.” Mullis is widely held as an eccentric who has shared his experiences, including his abduction by extraterrestrials.

Eleni Papadopulos-Eleopulos, a medical physicist based at the Royal Perth Hospital published a paper in 1988 declaring that HIV had never been correctly isolated as a distinct ‘pure’ virus. Along with Valendar Turner and John Papadimitriou, this group proclaims that HIV does not even exist! Like Duesberg, they say that drugs, poverty, and HIV medications cause AIDS. They also broaden their view by claiming other sources of immune suppression can lead to AIDS, such as repeated exposure to semen among gay men, although seemingly not women. They propose that an oxidation process occurs in response to HIV/AIDS risk factors, such as drug use, malnutrition, and exposure to semen that causes immune suppression and ultimately AIDS.

Etienne de Harven retired from the University of Toronto and having been a Professor of Cell Biology at Sloan Kettering Institute New York from 1956 to 1981. de Harven isolated and conducted electron microscopic studies of the murine (mouse) friend leukemia virus. He was also a member of the 2000 South Africa’s Presidential AIDS Advisory Panel and is a recognized leader among AIDS Rethinkers. He worked as a scientist in his field from the 1950’s until he retired. He challenged the proof that HIV has been isolated, according to the standards laid down by him. de Harven has said, “Dominated by the media, by special pressure groups and by the interests of several pharmaceutical companies, the AIDS establishment efforts to control the disease lost contact with open-minded, peer-reviewed medical science since the unproven HIV/AIDS hypothesis received 100% of the research funds while all other hypotheses were ignored.”

Christine Maggiore was the founder of Alive & Well, and was perhaps the most visible and visited HIV/AIDS denialist website. She tested HIV positive and remained untreated. Her three-year-old daughter Eliza Jane Scovill died of complications of AIDS whereas second opinions state that the death was the result of an adverse reaction to antibiotics. Maggiore founded Alive & Well in 1995 and wrote What If Everything You Thought You Knew about AIDS Was Wrong? Her story was portrayed on the popular US television show “Law & Order SVU” in October 2008. Christine Maggiore died of AIDS just a couple months later in December 2008. She is no longer with us, but her harmful legacy lives on.

Celia Farber is a journalist who has chronicled the Peter Duesberg phenomenon since the late 1980s. She has a personal relationship with Bob Guccione the founder of Penthouse Magazine and owner of Penthouse Media Group, Inc. affording Farber considerable access to the publishing world. In 1987, Farber began writing and editing a monthly investigative feature column “Words from the Front” in SPIN Magazine, owned by Guccione. She has been featured in Discover Magazine, also owned by Guccione. These articles focused on the critiques of HIV/AIDS science. In 2006 she published an article “Out of control: AIDS and the corruption of medical science” in Harper’s magazine which stirred interest as the article represented a breakthrough of HIV/AIDS denialism into mainstream media. The article is also a chapter in her book, Serious Adverse Events: An Uncensored History of AIDS, a collection of her magazine articles, mostly from the 1980s and 1990s. Farber has taken Duesberg on as a cause and in so doing has engaged in several rather nasty exchanges with AIDS scientists, most notably Robert Gallo. Along with Duesberg, Farber received a 2008 Clean Hands Award from the Semmelweis Society for her speaking out about the truth in AIDS. She has most recently filed a libel lawsuit against an HIV treatment advocacy group in New York City.

RW: Some people say that AIDS denial is a fringe ideology, that only affects a tiny group of people. What would you say to that?

I would say that it is true that AIDS denialism is a fringe ideology and that a fairly small group of people are actively involved in propagating AIDS denial. However, there is considerable evidence that that significant numbers of people are affected by AIDS denial. We know that in the US over 40% of Gay men question whether HIV is the cause of AIDS. We know that a majority of people who should be tested for HIV refuse. We know that people turn to the Internet for AIDS information and find AIDS denialism on numerous websites. We know that people are vulnerable to confusing information, especially when it is something that anyone would want to hear, such as HIV is not the cause of AIDS. There is no telling how many people have been harmed by AIDS denialism or how many listen to them. Whether it be thousands or hundreds of thousands who listen to AIDS denialists, we know from the South African experience that if just one person with power to make decisions listens the results can be devastating.

RW: In “Denying AIDS” you make comparisons between AIDS denial and other fringe ideologies – could you tell us a bit more about that?

The similarities between AIDS denialism and cancer denialism, Holocaust Denial, 9/11 Truth Seeking, and Global Warming Denial are striking. All of these groups use the same tactics to create the impression that experts disagree and that the historical record is in dispute. They all use selective information taken out of context that supports their viewpoint. They ignore facts and propel myths. They include pseudo-experts. They rely on conspiracy theories to gain attention. They are persuasive in their rhetoric. They use books to circumvent peer-review, they create their own periodicals, and they produce documentary looking films. They also effectively use the Internet and have manipulated their way into mainstream media. In some cases, they are even the same people! I believe that there is a denialism prone personality that I discuss in Denying AIDS. People who approach the world from a suspicious stance, are anti-establishment, and somewhat grandiose are among those who are prone to denialism.

RW: What is the relationship between AIDS denial and alternative medicine?

Not all AIDS denialists sell alternative treatments, but some do. However, all AIDS denialists pave the path for fraudulent cures and snake oil treatments. AIDS denialist say that HIV does not cause AIDS, leaving open the question of what should be done to treat AIDS? Among the most notorious AIDS denialists are those who sell remedies, such as Matthias Rath and Gary Null who sell vitamins and nutritional supplements they have proclaimed treat HIV/AIDS. Ben Goldacre has written about Matthias Rath’s destructive profiteering in his book Bad Science. AIDS denialists have on occasion worked closely with these vitamin entrepreneurs, as was the case when American David Rasnick and South African Anthony Brink teamed up with Matthias Rath. Of course, many people make well informed decisions and choose to complementary treatments such as nutritional supplements and vitamins as part of their HIV-related health care. Indeed, people may even make informed decisions to forego anti-HIV mediations. I believe we should respect these decisions when they are well-informed. HIV treatments are not for everyone. The problem we have with AIDS denialism is that it misinforms people and steers them away from HIV treatments. People are therefore being deceived by denialism to make misinformed decisions, and that of course is not okay.

RW: What did you come across in the course of your research that especially surprised you?

It surprised me that the AIDS denialists truly believe what they are saying. I had thought that they must be blatant liars and scam artists. Perhaps some are. But I have come to realize that most AIDS denialists really believe that HIV does not cause AIDS. They tend to be paranoid and their suspicious cognitive style bends facts to fit their preconceived notions. I will never forget when Peter Duesberg looked me dead in the eyes and said “You know, there is no vaccine for this; it is not an infectious disease.” I have no question that he believes what he says, as mad as it is.

Seth C. Kalichman is a Professor of Psychology at the University of Connecticut, and the Editor of the journal AIDS and Behavior. His new book is “Denying AIDS: Conspiracy Theories, Pseudoscience, and Human Tragedy”; royalties are donated to buy HIV meds in Africa. http://denyingaids.blogspot.com

Steve Salerno on the perils of “positive thinking”

From The Skeptic

Like many of the touchy-feely messages that flood modern America, The Secret is about the rejection of the “inconvenient” truths of the physical world. In the broad culture, science and logic have fallen out of fashion. We are, after all, a people who increasingly abandon orthodox medicine for mind-body regimens whose own advocates not only refuse to cite clinical proof, but dismiss science itself as “disempowering.” (The rallying cry that “you have within you the energies you need to heal” is one reason why visits to practitioners of all forms of alternative medicine now outnumber visits to traditional family doctors by a margin approaching two-to-one.) What I find most remarkable about The Secret, however, is that it somehow mainstreamed the solipsistic “life is whatever you think it is” mindset that once was associated with mental illnesses like schizophrenia. The Secret was (and remains) the perfect totem for its time, uniquely captivating two polar generations: Baby Boomers reaching midlife en masse and desperate to unshackle themselves from everything they’ve been until now; and young adults weaned on indulgent parenting and — especially — indulgent schooling.

Indeed, if there was a watershed moment in modern positive thinking, it would have to be the 1970s advent of self-esteem-based education: a broad-scale social experiment that made lab rats out of millions of American children. At the time, it was theorized that a healthy ego would help students achieve greatness (even if the mechanisms required to instill self-worth “temporarily” undercut traditional scholarship). Though back then no one really knew what self-esteem did or didn’t do, the nation’s educational brain trust nonetheless assumed that the more kids had of it, the better.

It followed that almost everything about the scholastic experience was reconfigured to support ego development and positivity about learning and life. To protect students from the ignominy of failure, schools softened criteria so that far fewer children could fail. Grading on a curve became more commonplace, even at the lowest levels; community-based standards replaced national benchmarks. Red ink began disappearing from students’ papers as administrators mandated that teachers make corrections in less “stigmatizing” colors. Guidance counselors championed the cause of “social promotion,” wherein underperforming grade-schoolers — instead of being left back — are passed along to the next level anyway, to keep them with their friends of like age.

There ensued a wholesale celebration of mediocrity: Schools abandoned their honor rolls, lest they bruise the feelings of students who failed to make the cut. Jean Twenge, author of Generation Me: Why Today’s Young Americans Are More Confident, Assertive, Entitled … and More Miserable Than Ever Before, tells of pizza parties that “used to be only for children who made A’s, but in recent years the school has invited every child who simply passed.” (Twenge also writes of teachers who were discouraged from making corrections that might rob a student of his pride as an “individual speller.”) Banned were schoolyard games that inherently produced winners and losers; there could be no losers in this brave new world of positive vibes.

Amid all this, kids’ shirts and blouses effectively became bulletin boards for a hodge-podge of ribbons, pins and awards that commemorated everything but real achievement. Sometimes, the worse the grades, the more awards a student got, under the theory that in order to make at-risk kids excel, you first had to make them feel optimistic and empowered.

…Tellingly, when psychologists Harold Stevenson and James Stigler compared the academic skills of grade-school students in three Asian nations to those of their U.S. peers, the Asians easily outdid the Americans — but when the same students then were asked to rate their academic prowess, the American kids expressed much higher self-appraisals than their foreign counterparts. In other words, U.S. students gave themselves high marks for lousy work. Stevenson and Stigler saw this skew as the fallout from the backwards emphasis in American classrooms; the Brookings Institution 2006 Brown Center Report on Education also found that nations in which families and schools emphasize self-esteem cannot compete academically with cultures where the emphasis is on learning, period.

Skeptics in the Pub – evidence-based-policy-making versus policy-based-evidence-making

Monday’s book talk at Skeptics in the Pub certainly wasn’t my best, though things warmed up a bit with the Q&A discussion at the end.

My main focus was on the value of scepticism in, and about, politics – and I put forward three key examples to try to illustrate this: the case of the Soviet pseudo-scientist Trofim Lysenko, the UK government’s misleading statements about Iraq’s “WMD”, and the South African authorities’ embrace of “AIDS denialism” in the year 2000.

All three of these cases arguably involved costly government decisions being made on the basis of bad evidence that had not been properly scrutinised.

Lysenko’s theories about agriculture were far-fetched and unworkable, but they were ideologically agreeable to the Communist regime, and after he rose to prominence the totalitarian nature of the Soviet system made it very difficult for anyone to challenge his authority. When Lysenko’s ideas were implemented in China, they contributed to a famine that is believed to have claimed up to 30 million lives.

The evidence cited by the UK government in support of its view that Iraq possessed chemical weapons was famously “dodgy”. It’s widely believed that the Prime Minister at the time, Tony Blair, lied about the strength of that evidence, and about the views of his own experts (many of whom, it later, transpired, had grave doubts about the claims being made), not only to the public at large and the UK’s Parliament, but also to many members of his own cabinet. One ex-minister, Clare Short, has suggested that Blair believed he was engaging in an “honorable deception” for the greater good. But whatever his motives, in lying to his own cabinet and Parliament, Blair was effectively shutting out of the decision-making process the very people whose job it is to scrutinise the evidence on which government policies are based. John Williams, one of the spin doctors involved in drawing up the famous “dodgy dossier” – which at the time the government insisted was the unvarnished view of the intelligence services – later admitted that “in hindsight we could have done with a heavy dose of scepticism” (though it should be said that some of his statements raise more questions than they answer).

In South Africa in the early part of this decade, President Thabo Mbeki chose to believe the unsubstantiated claims of fringe scientists and conspiracy theorists over those of established AIDS researchers – including members of South Africa’s own scientific community. Under the influence of denialists who insist that HIV is not the cause of AIDS, and that AIDS deaths are in fact caused by the lifesaving medicines given to people with HIV, Mbeki’s government chose to block the availability of anti-retroviral drugs in South Africa – even after the pharmaceutical companies had been shamed into slashing their prices and international donors were offering to fund the distribution. It was only after a series of court cases by the indefatigable Treatment Action Campaign that, in 2004, the authorities began to change their position. A recent study by Harvard University concluded that the deliberate obstruction of the roll-out of lifesaving drugs may have cost more than 300,000 lives.

The broad conclusion I think all of this points to is that the truth matters more in politics than ever before. Because of power and influence that governments now hold, the consequences of a bad policy implemented on the basis of bad evidence can adversely affect millions.

In an ideal world governments would be engaging in evidence-based-policy-making: deciding policy on the basis of the best available evidence – rather than policy-based-evidence-making: cherry-picking or concocting evidence to support a decision that has already been made. But obviously this doesn’t always happen, and as a result wholly preventable mistakes continue to be made.

Book talk – Sceptics in the Pub, Monday April 27th

Book talk – Sceptics in the Pub, 7pm, Monday April 27th

The Penderel’s Oak pub

283–288 High Holborn

Holborn

London

WC1V 7HP (map)

Given the disasters, human and financial, that can result when governments lose their grip on reality, it’s arguably in politics that skepticism matters most. Yet from Thabo Mbeki’s disastrous dalliance with AIDS denial in South Africa, to the delusions that led to the Iraq war, our politicians often seem perilously credulous. In “Don’t Get Fooled Again“, Richard Wilson looks at why it is that intelligent, educated people end up time and again falling for ideas that turn out to be nonsense, and makes the case for skeptics to be actively engaged with the political process.

A Place At the Table – Camden People’s Theatre April 16th – May 2nd

From Indie London

DAEDALUS Theatre is presenting A Place at the Table at Camden People’s Theatre – from April 15 to May 2, 2009…

A Place at the Table draws on Burundian traditions and mythology and varying accounts of the recent history of the Great Lakes region of Africa in what is described as a bold new work of visual and verbatim theatre.

The international company includes artists from Burundi, Rwanda, Uganda and Democratic Republic of Congo, and campaigner Richard Wilson, who has spoken on and written about Burundi extensively since his sister, Charlotte Wilson, was killed in the country in the year 2000, is an advisor.

Performers include Naomi Grosset, Lelo Majozi-Motlogeloa, Jennifer Muteteli, Anna-Maria Nabirya, Susan Worsfold and Grace Nyandoro (singer).

Melchior Ndadaye, the first democratically elected president of Burundi, was assassinated in October 1993, just three months after his election. His assassination was one of the root causes of the subsequent ten year civil war in Burundi, and is closely tied to the causes and effects of several other conflicts in Rwanda and Democratic Republic of Congo, particularly those related to Hutu and Tutsi ethnicity.

A Place at the Table is directed, designed and produced by Paul Burgess, who has recently designed Cradle Me (Finborough Theatre), Our Country’s Good (Watermill Theatre), On the Rocks (Hampstead Theatre), Triptych (Southwark Playhouse), The Only Girl in the World (Arcola Theatre) and Jonah and Otto (Manchester Royal Exchange).